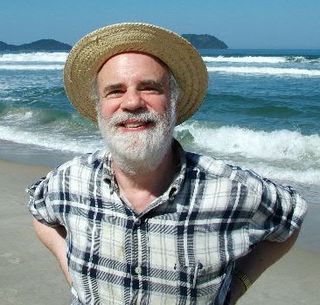

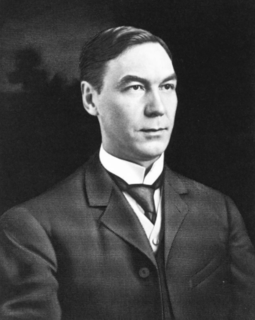

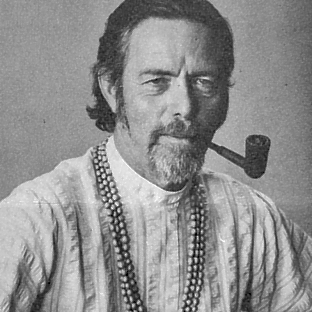

A Quote by Saul Kripke

In fact, of course, I hold that propositions that contemporary

philosophers would properly count as 'empirical' can be necessary and be known to be such.

Related Quotes

The propositions of mathematics have, therefore, the same unquestionable certainty which is typical of such propositions as "All bachelors are unmarried," but they also share the complete lack of empirical content which is associated with that certainty: The propositions of mathematics are devoid of all factual content; they convey no information whatever on any empirical subject matter.

Unfortunately, philosophers of science usually regard scientific realism and scientific anti-realism as monistic doctrines. The assumption is that there is one goal of all scientific inference - finding propositions that are true, or finding propositions that are predictively accurate. In fact, there are multiple goals. Sometimes realism is the right interpretation of a scientific problem, while at other times instrumentalism is.

I had no idea what philosophy was until I went to college at UBC. I first read Hume and Plato, so naturally I was under the misapprehension that philosophers are trying to figure out what is true, and that contemporary philosophers are mainly trying to figure out what is true about the mind. Of course Hume and Plato were trying to do that, hence my misapprehension.

Philosophers often think all scientists must be scientific realists. If you ask a simple question like "Are electrons real?" the answer will be "Yes". But if your questions are less superficial, for example whether some well-known scientist was a good scientist. Then, they had insisted that only empirical criteria matter and that they actually did not believe in the reality of sub-atomic entities. Ask "If that turned out to be true, would you still say they were good scientists?" The answer would reveal something about how they themselves understood what it is to be a scientist.

There are different interpretations of the problem of universals. I understand it as the problem of giving the truthmakers of propositions to the effect that a certain particular is such and such, e.g. propositions like 'this rose is red'. Others have interpreted it as a problem about the ontological commitments of such propositions or a problem about what those propositions mean.

It is time, therefore, to abandon the superstition that natural science cannot be regarded as logically respectable until philosophers have solved the problem of induction. The problem of induction is, roughly speaking, the problem of finding a way to prove that certain empirical generalizations which are derived from past experience will hold good also in the future.

The finest imagination in the world could not have conceived of a better idea than the philosophers' stone to inspire the minds and faculties of men. Without it, chemistry would not be what it is today. In order to discover that no such thing as the philosopher's stone existed, it was necessary to ransack and analyze every substance known on earth. And in precisely this lay its miraculous influence.