A Quote by Seneca the Younger

Nature has given us the seeds of knowledge, not knowledge itself.

Related Quotes

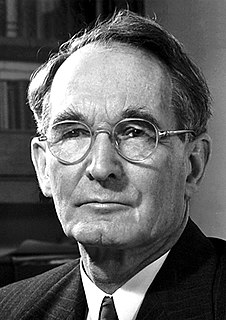

The knowledge we now consider knowledge proves itself in action. What we now mean by knowledge is information effective in action, information focused on results. Results are outside the person, in society and economy, or in the advancement of knowledge itself. To accomplish anything this knowledge has to be highly specialized.

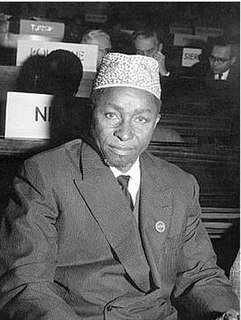

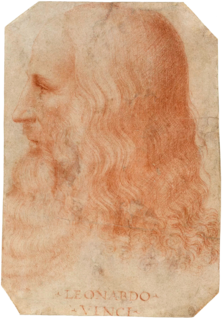

In order to arrive at knowledge of the motions of birds in the air, it is first necessary to acquire knowledge of the winds, which we will prove by the motions of water in itself, and this knowledge will be a step enabling us to arrive at the knowledge of beings that fly between the air and the wind.

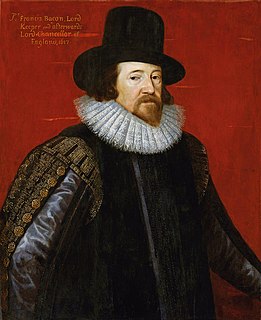

I am convinced that it is impossible to expound the methods of induction in a sound manner, without resting them upon the theory of probability. Perfect knowledge alone can give certainty, and in nature perfect knowledge would be infinite knowledge, which is clearly beyond our capacities. We have, therefore, to content ourselves with partial knowledge - knowledge mingled with ignorance, producing doubt.

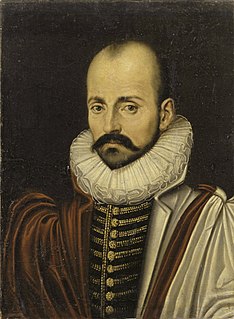

Surely knowledge of the natural world, knowledge of the human condition, knowledge of the nature and dynamics of society, knowledge of the past so that one may use it in experiencing the present and aspiring to the future--all of these, it would seem reasonable to suppose, are essential to an educated man. To these must be added another--knowledge of the products of our artistic heritage that mark the history of our esthetic wonder and delight.

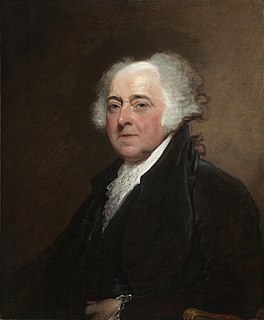

And liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people who have a right from the frame of their nature to knowledge, as their great Creator who does nothing in vain, has given them understandings and a desire to know. But besides this they have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible divine right to the most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge, I mean of the characters and conduct of their rulers.

Nature is seen by humans through a screen of beliefs, knowledge, and purposes, and it is in terms of their images of nature, rather than of the actual structure of nature, that they act. Yet, it is upon nature itself that they do act, and it is nature itself that acts upon them, nurturing or destroying them.

But if men would give heed to the nature of substance they would doubt less concerning the Proposition that Existence appertains to the nature of substance: rather they would reckon it an axiom above all others, and hold it among common opinions. For then by substance they would understand that which is in itself, and through itself is conceived, or rather that whose knowledge does not depend on the knowledge of any other thing.

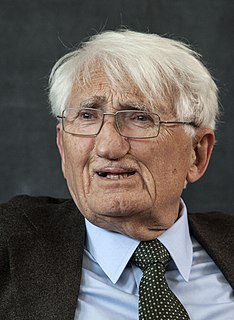

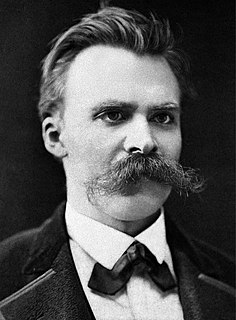

We should not be content to say that power has a need for such-and-such a discovery, such-and-such a form of knowledge, but we should add that the exercise of power itself creates and causes to emerge new objects of knowledge and accumulates new bodies of information. ... The exercise of power perpetually creates knowledge and, conversely, knowledge constantly induces effects of power. ... It is not possible for power to be exercised without knowledge, it is impossible for knowledge not to engender power.

First, In showing in how to avoid attempting impossibilities. Second, In securing us from important mistakes in attempting what is, in itself possible, by means either inadequate or actually opposed to the end in view. Thirdly, In enabling us to accomplish our ends in the easiest, shortest, most economical, and most effectual manner. Fourth, In inducing us to attempt, and enabling us to accomplish, object which, but for such knowledge, we should never have thought of understanding.

On the ways that a knowledge of the order of nature can be of use.