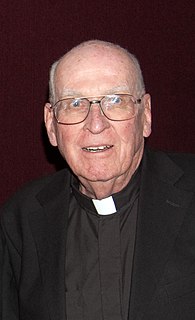

A Quote by Stanley B. Prusiner

From the point of view of many scientists, gods represent an explanation for the unknown. Scientists are focused on trying to understand the unknown, so there is a fundamental conflict. That said, some scientists find religion useful and perhaps even fulfilling.

Related Quotes

Scientists are people of very dissimilar temperaments doing different things in very different ways. Among scientists are collectors, classifiers and compulsive tidiers-up; many are detectives by temperament and many are explorers; some are artists and others artisans. There are poet-scientists and philosopher-scientists and even a few mystics.

You ask people, do you pray to [a person or] God. If you say yes to that, you're religious by, presumably, anybody's standards of your conduct. And it's the yes to that question that applies to 40% of scientists. So, there're plenty of atheists who are scientists or not scientists. There maybe a conflict but many people in this country coexist in both worlds.

I'm a skeptic. ...Global Warming it's become a new religion. You're not supposed to be against Global Warming. You have basically no choice. And I tell you how many scientists support that. But the number of scientists is not important. The only thing that's important is if the scientists are correct; that's the important part.

The government employs scientists of many varieties in technical capacities, from estimating the environmental toxicity of a chemical to the structural soundness of a bridge. But when it comes to forming policies, these scientists and, especially, behavioral scientists are rarely at the table with the lawyers and the economists.

People often think of artists and scientists as being diametrically opposed, but we both believe something is possible. We have a hypothesis and then we do everything to make it possible, but we don't know if it's possible! All the scientists I've worked with have a natural, easy fit with me. The solutions they find are truly creative. All scientists, in some way, are artists.

I feel very strongly indeed that a Cambridge education for our scientists should include some contact with the humanistic side. The gift of expression is important to them as scientists; the best research is wasted when it is extremely difficult to discover what it is all about ... It is even more important when scientists are called upon to play their part in the world of affairs, as is happening to an increasing extent.

It is the job of artists to open doors and invite in prophesies, the unknown, the unfamiliar; it’s where their work comes from, although its arrival signals the beginning of the long disciplined process of making it their own. Scientists too, as J. Robert Oppenheimer once remarked, ‘live always at the ‘edge of mystery’—the boundary of the unknown.’ But they transform the unknown into the known, haul it in like fishermen; artists get you out into that dark sea.

Scientists and theologians can’t offer better than circular arguments, because there are no other kinds of arguments. Bible believers quote the Bible, and scientists quote other scientists. How do either scientists or theologians answer this question about the accuracy of their conclusions: “In reference to what?