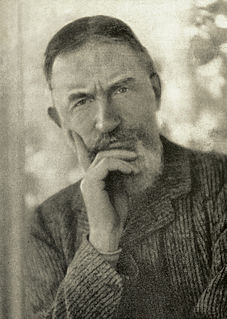

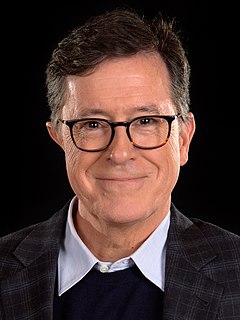

A Quote by Stephen Fry

It is astonishing how articulate one can become when alone and raving at a radio. Arguments and counter arguments, rhetoric and bombast flow from one's lips like scurf from the hair of a bank manager.

Related Quotes

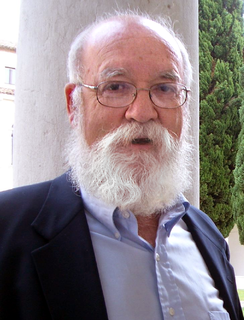

Highly technical philosophical arguments of the sort many philosophers favor are absent here. That is because I have a prior problem to deal with. I have learned that arguments, no matter how watertight, often fall on deaf ears. I am myself the author of arguments that I consider rigorous and unanswerable but that are often not such much rebutted or even dismissed as simply ignored.

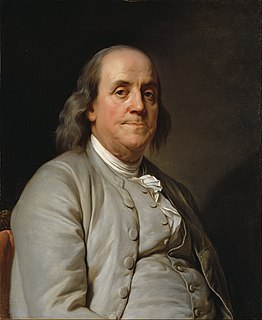

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech - the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice.

When confronted with two courses of action I jot down on a piece of paper all the arguments in favor of each one, then on the opposite side I write the arguments against each one. Then by weighing the arguments pro and con and cancelling them out, one against the other, I take the course indicated by what remains.

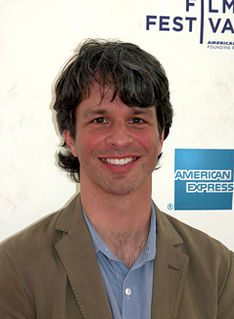

Most of this film, however, is about interpretation - are these people terrorists or freedom fighters? Are they good or bad? Is cutting timber good or bad? And I don't feel like the answers to those questions are simple, so we don't try to answer them for the audience. I wanted to elicit the strongest - and most heartfelt - arguments from the characters in the film and let those arguments bang up against the strongest arguments of their opponents.