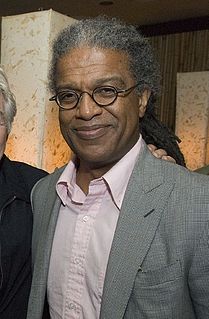

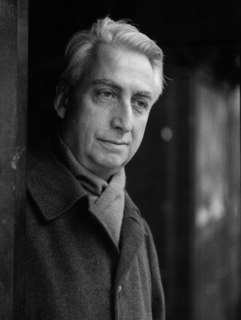

A Quote by Terry Teachout

Yes, translation is by definition an inadequate substitute for being able to read a masterpiece in the original.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Yes. The original argument is defective. Substitute the word 'male' for 'gay,' and you'll see the flaw: 'Male people cannot be normal. If everyone were male starting tomorrow, the human race would die out, so being male cannot be nature's intended way.' Or you could substitute the word 'female.' In either case, the argument makes no sense: Being male or female is perfectly normal.

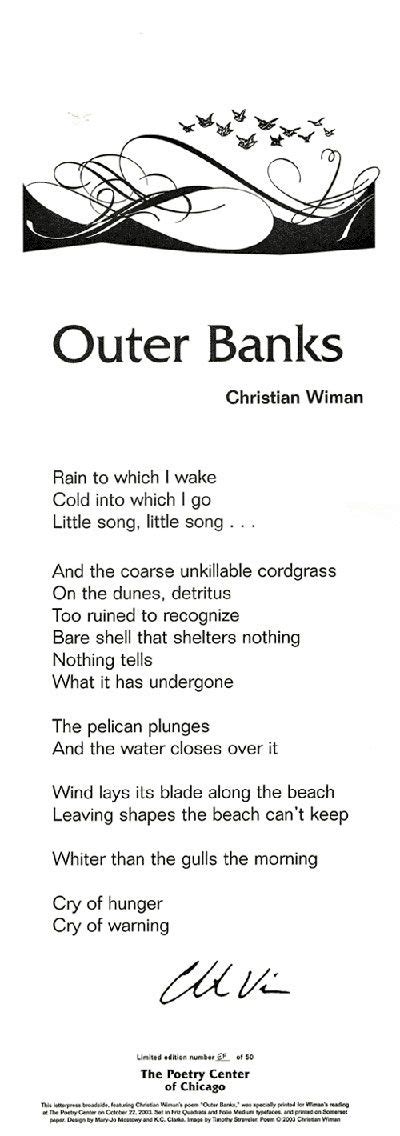

There is an old Italian proverb about the nature of translation: "Traddutore, traditore!" This means simply, "Translators-traitors!" Of course, as you can see, something is lost in the translation of this pithy expression: there is great similarity in both the spelling and the pronunciation of the original saying, but these get diluted once they are put in English dress. Even the translation of this proverb illustrates its truth!

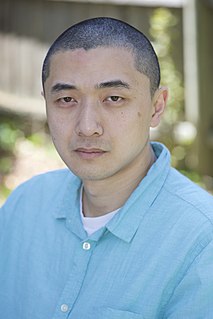

I've had the good fortune to read a lot of great American writers in translation, and my absolute beloved, for me one of the greatest writers ever, is Mark Twain. Yes, yes, yes. And Whitman, from whom the whole of 20th-century poetry sprung up. Whitman was the origin of things, someone with a completely different outlook. But I think that he's the father of the new wave in the world's poetry which to this very day is hitting the shore.