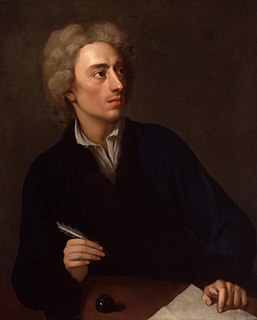

A Quote by Thomas Gray

The language of the age is never the language of poetry, except among the French, whose verse, where the thought or image does not support it, differs in nothing from prose.

Related Quotes

Verse in itself does not constitute poetry. Verse is only an elegant vestment for a beautiful form. Poetry can express itself in prose, but it does so more perfectly under the grace and majesty of verse. It is poetry of soul that inspires noble sentiments and noble actions as well as noble writings.

We believe we can also show that words do not have exactly the same psychic "weight" depending on whether they belong to the language of reverie or to the language of daylight life-to rested language or language under surveillance-to the language of natural poetry or to the language hammered out by authoritarian prosodies.

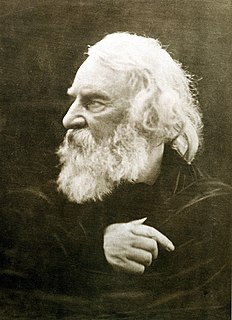

Poetry cannot be translated; and, therefore, it is the poets that preserve the languages; for we would not be at the trouble to learn a language if we could have all that is written in it just as well in a translation. But as the beauties of poetry cannot be preserved in any language except that in which it was originally written, we learn the language.

She alone dares and wishes to know from within, where she, the outcast, has never ceased to hear the resonance of fore language. She lets the other language speak - the language of 1,000 tongues which knows neither enclosure nor death. To life she refuses nothing. Her language does not contain, it carries; it does not hold back; it makes possible.