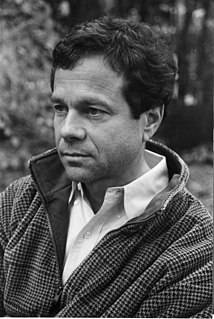

A Quote by Tim Hunt

I am extremely sorry for the remarks made during the recent Women in Science lunch at the world conference of science journalists in Seoul, Korea.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

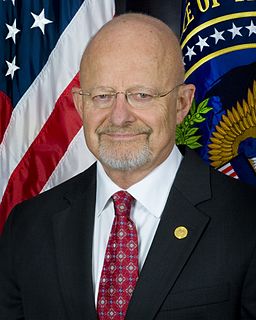

If we - particularly, if we peremptorily attack North Korea - that without deliberation, that North Korea will reflexively unleash all the rocketry and artillery - which they're pretty good at, by the way - on Seoul, and do as they vowed many times, to convert Seoul into a sea of fire. So, if we do something like this, this will have cataclysmic results.

Yes, yes, I see it all! — an enormous social activity, a mighty civilization, a profuseness of science, of art, of industry, of morality, and afterwords, when we have filled the world with industrial marvels, with great factories, with roads, museums and libraries, we shall fall exhausted at the foot of it all, and it will subsist — for whom? Was man made for science or was science made for man?

The Genealogical Science is a wonderful account of how old-fashioned race science has come to be re-defined by resort to the most recent developments in genetics. But this book is not simply another story of the ideological uses to which science may be put. Nadia Abu El-Haj has provided the reader with a very detailed analysis of the historical entanglement between science and politics. Her study should be required reading for anyone interested in the sociology of science-and also for those dealing with Middle Eastern nationalisms. This is a work of outstanding value for scholarship.

The life and soul of science is its practical application, and just as the great advances in mathematics have been made through the desire of discovering the solution of problems which were of a highly practical kind in mathematical science, so in physical science many of the greatest advances that have been made from the beginning of the world to the present time have been made in the earnest desire to turn the knowledge of the properties of matter to some purpose useful to mankind.