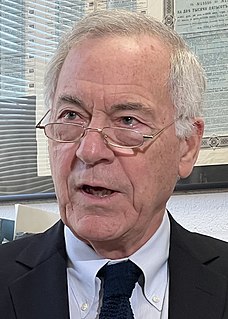

A Quote by Urjit Patel

The two important variables for the policy formulation are projected inflation and the output gap. There is no clear hidebound mathematics that we must give 'X' weight to inflation and 'Y' weight to growth and form the associated policy.

Related Quotes

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output... A steady rate of monetary growth at a moderate level can provide a framework under which a country can have little inflation and much growth. It will not produce perfect stability; it will not produce heaven on earth; but it can make an important contribution to a stable economic society.

Inflation is certainly low and stable and, measured in unemployment and labour-market slack, the economy has made a lot of progress. The pace of growth is disappointingly slow, mostly because productivity growth has been very slow, which is not really something amenable to monetary policy. It comes from changes in technology, changes in worker skills and a variety of other things, but not monetary policy, in particular.

[Australian Reserve Bank] Governor MacFarlane said recently when Paul Volcker broke the back of American inflation it's regarded as the policy triumph of the Western world. When I broke the back of Australian inflation they say, "Oh, you're the fellow that put the interest rates up." Am I not the same fellow that gave them the 15 years of good growth and high wealth that came from it?

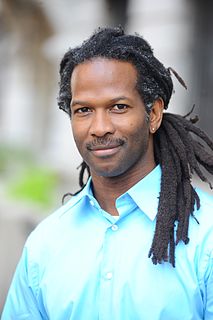

The policy that received more attention particularly in the past decade and a half or so has been the US cocaine policy, the differential treatment of crack versus powder cocaine and question is how my research impacted my view on policy. Clearly that policy is not based on the weight of the scientific evidence. That is when the policy was implemented, the concern about crack cocaine was so great that something had to be done and congress acted in the only way they knew how, they passed policy and that's what a responsible society should do.

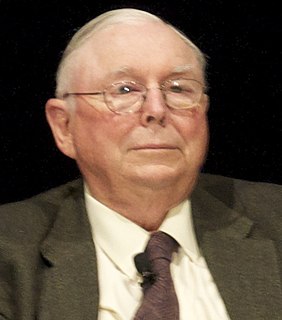

Significant changes in the growth rate of money supply, even small ones, impact the financial markets first. Then, they impact changes in the real economy, usually in six to nine months, but in a range of three to 18 months. Usually in about two years in the US, they correlate with changes in the rate of inflation or deflation."

"The leads are long and variable, though the more inflation a society has experienced, history shows, the shorter the time lead will be between a change in money supply growth and the subsequent change in inflation.

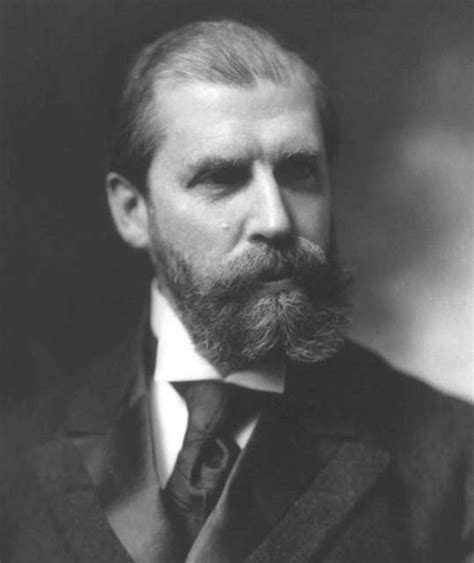

I think democracies are prone to inflation because politicians will naturally spend [excessively] - they have the power to print money and will use money to get votes. If you look at inflation under the Roman Empire, with absolute rulers, they had much greater inflation, so we don't set the record. It happens over the long-term under any form of government.