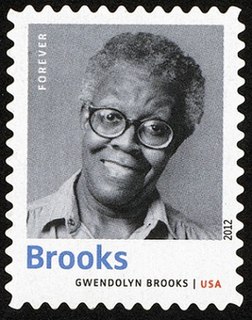

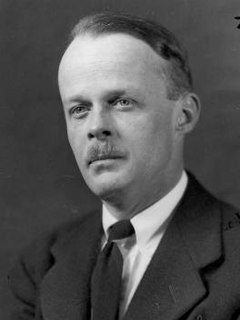

A Quote by W. H. Auden

It has been said that a poem should not mean but be. This is not quite accurate. In a poem, as distinct from many other kinds of verbal societies, meaning and being are identical. A poem might be called a pseudo-person. Like a person, it is unique and addresses the reader personally. On the other hand, like a natural being and unlike a historical person, it cannot lie.

Related Quotes

I keep feeling that there isn't one poem being written by any one of us - or a book or anything like that. The whole life of us writers, the whole product I guess I mean, is the one long poem - a community effort if you will. It's all the same poem. It doesn't belong to any one writer - it's God's poem perhaps. Or God's people's poem.

I want each poem to be ambiguous enough that its meaning can shift, depending on the reader's own frame of reference, and depending on the reader's mood. That's why negative capability matters; if the poet stops short of fully controlling each poem's meaning, the reader can make the poem his or her own.

Theology is-- or should be-- a species of poetry,which read quickly or encountered in a hubbub of noise makes no sense. You have to open yourself to a poem with a quiet, receptive mind, in the same way you might listen to a difficult piece of music... If you seize upon a poem and try to extort its meaning before you are ready, it remains opaque. If you bring your own personal agenda to bear upon it, the poem will close upon itself like a clam, because you have denied its unique and separate identity, its inviolate holiness.

Reading a poem is a real thing, a worthy thing. So to be there right with the reader at that moment is part of the effect of a title like "Poem for" something or other. Matt Rohrer does this a lot in his titles, and I think I might have gotten some of the idea to do this, or at least been reminded of how it can work, from his recent amazing books.

The subject of the poem usually dictates the rhythm or the rhyme and its form. Sometimes, when you finish the poem and you think the poem is finished, the poem says, "You're not finished with me yet," and you have to go back and revise, and you may have another poem altogether. It has its own life to live.

The poem is not, as someone put it, deflective of entry. But the real question is, 'What happens to the reader once he or she gets inside the poem?' That's the real question for me, is getting the reader into the poem and then taking the reader somewhere, because I think of poetry as a kind of form of travel writing.