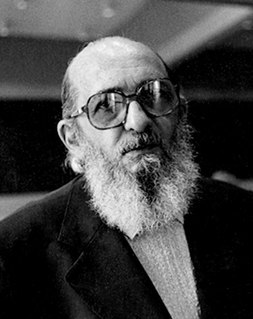

A Quote by Walter Benjamin

The power of a text when it is read is different from the power it has when it is copied out. Only the copied text thus commands the soul of him who is occupied with it, whereas the mere reader never discovers the new aspects of his inner self that are opened by the text, that road cut through the interior jungle forever closing behind it: because the reader follows the movement of his mind in the free flight of day-dreaming, whereas the copier submits it to command.

Related Quotes

We must be forewarned that only rarely does a text easily lend itself to the reader's curiosity... the reading of a text is a transaction between the reader and the text, which mediates the encounter between the reader and writer. It is a composition between the reader and the writer in which the reader "rewrites" the text making a determined effort not to betray the author's spirit.

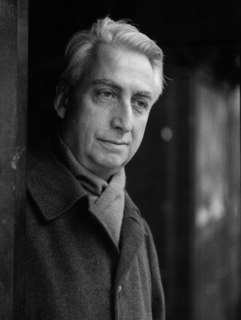

And so, when I began to read the proffered pages, I at one moment lost the train of thought in the text and drowned it in my own feelings. In these seconds of absence and self-oblivion, centuries passed with every read but uncomprehended and unabsorbed line, and when, after a few moments, I came to and re-established contact with the text, I knew that the reader who returns from the open seas of his feelings is no longer the same reader who embarked on that sea only a short while ago.

The meaning of a work is not what the author had in mind at some point, nor is it simply a property of the text or the experience of a reader. Meaning is an inescapable notion because it is not something simple or simply determined. It is simultaneously an experience of a subject and a property of a text. It is both what we understand and what in the text we try to understand.

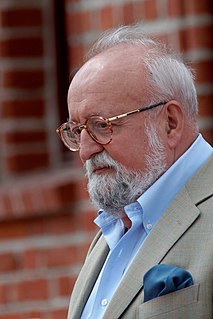

With Orff it is text, text, text - the music always subordinate. Not so with me. In 'Magnificat,' the text is important, but in some places I'm writing just music and not caring about text. Sometimes I'm using extremely complicated polyphony where the text is completely buried. So no, I am not another Orff, and I'm not primitive.

So we start with an oversignifying reader. Those texts that appear to reward this reader for this additional investment - text that we find exceptionally suggestive, apposite, or musical - are usually adjudged to be 'poetic'. ... The work of the poet is to contribute a text that will firstly invite such a reading; and secondly reward such a reading.

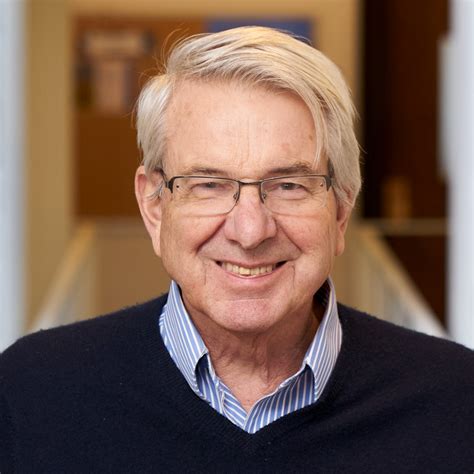

One of the things I really respect about Doug Moo is that he is constantly grappling with the text. Where he hears the text saying something which is not what his tradition would have said, he will go with the text. I won't always agree with his exegesis, but there is a relentless scholarly honesty about him which I really tip my hat off to.

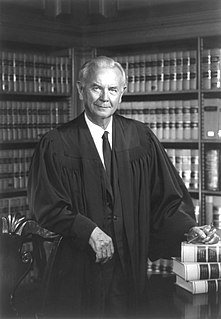

Our amended Constitution is the lodestar for our aspirations. Like every text worth reading, it is not crystalline. The phrasing is broad and the limitations of its provisions are not clearly marked. Its majestic generalities and ennobling pronouncements are both luminous and obscure. This ambiguity of course calls forth interpretation, the interaction of reader and text. The encounter with the Constitutional text has been, in many senses, my life's work.

We've clearly entered a period in which the analog of text is no longer important or relevant. All text will be electronic. I accept that fact. My house has thousands of books in it, and I've started to look at them completely differently. They now seem to me to be like antiquarian objects. Their use value has become negligible to me because I'm perfectly happy to read on an e-reader.