A Quote by Zadie Smith

Every genuinely literary style, from the high authorial voice to Foster Wallace and his footnotes-within-footnotes, requires the reader to see the world from somewhere in particular, or from many places. So every novelist's literary style is nothing less than an ethical strategy - it's always an attempt to get the reader to care about people who are not the same as he or she is.

Related Quotes

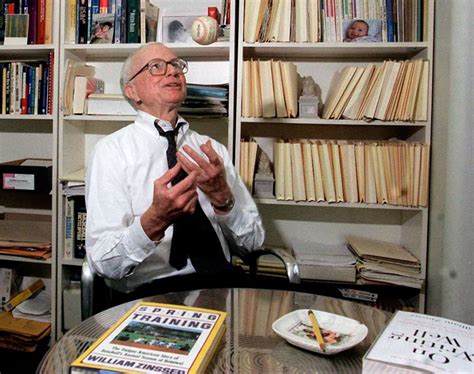

With the audience I write for, I want to make sure that the reader is eagerly turning every page. I want each of my books to be an absorbing reading experience, an authentic piece of literature. The worst thing that can happen is for a book to have a chilling effect on the reader, to have a kid pick it up and look at a bunch of footnotes and think, No, I'm not going to read this, it's too intimidating.

I actually dislike, more than many people, working through literary allusion. I just feel that there's something a bit snobbish or elitist about that. I don't like it as a reader, when I'm reading something. It's not just the elitism of it; it jolts me out of the mode in which I'm reading. I've immersed myself in the world and then when the light goes on I'm supposed to be making some kind of literary comparison to another text. I find I'm pulled out of my kind of fictional world, I'm asked to use my brain in a different kind of way. I don't like that.

If I may bend your ear for a moment, I like Terry Pratchett. I like footnotes. I like footnotes even when they are not as entertaining as a Pratchett footnote, even when they are in the middle of a book on evolutionary biology and briefly explain the Red Queen hypothesis or the fate of the Stephen's Island Wren or how many bunnies can dance on the back of Australia. Footnotes fill me with a very mild glee. The endnote simply does not compare.

Good writing is good writing. In many ways, it’s the audience and their expectations that define a genre. A reader of literary fiction expects the writing to illuminate the human condition, some aspect of our world and our role in it. A reader of genre fiction likes that, too, as long as it doesn’t get in the way of the story.

It is easier for the reader to judge, by a thousand times, than for the writer to invent. The writer must summon his Idea out of nowhere, and his characters out of nothing, and catch words as they fly, and nail them to the page. The reader has something to go by and somewhere to start from, given to him freely and with great generosity by the writer. And still the reader feels free to find fault.