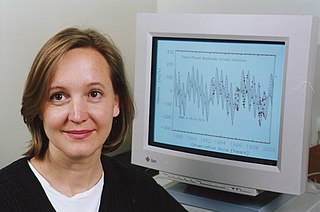

A Quote by Debra Fischer

Before 1995, the only planets we knew about were the planets in our solar system.

Related Quotes

When I grew up as a kid, we didn't know there were any other planets outside of our own solar system. It was widely speculated that planet formation was an incredibly rare event and that it's possible that other planets just don't exist in our galaxy, and it's just this special situation where we happen to have planets around our sun.

There's no doubt that the search for planets is motivated by the search for life. Humans are interested in whether or not life evolves on other planets. We'd especially like to find communicating, technological life, and we look around our own solar system, and we see that of all the planets, there's only one that's inhabited.

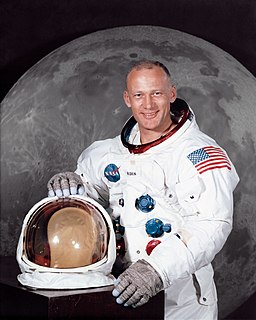

When Hubble was launched, it became clear very shortly thereafter that there was a problem with the optics.The mirror was not quite the right shape. And the one program that I had really been looking forward to doing with Hubble was studying outer planets in our solar system, the planets Uranus and Neptune.

We know there are billions of stars and planets literally out there, and the universe is getting bigger. We know from our fancy telescopes that just in the last two years more than 20 planets have been identified outside our solar system that seem to be far enough away from their suns - - and dense enough - - that they might be able to support some form of life. So it makes it increasing less likely that we're alone. But if we were visited someday, I wouldn't be surprised.