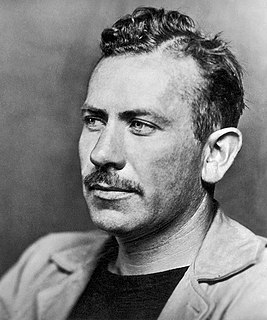

A Quote by John Steinbeck

If we could learn even a little to like ourselves, maybe our cruelties and angers might melt away.

Related Quotes

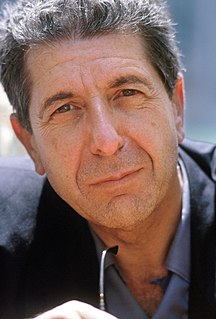

Maybe we, the cultural workers , could apply ourselves. We're not going to resolve it in this moment or even in this generation, but perhaps as some kind of agenda we could invite our writers and cultural workers to address the problem a little more responsibly, because people are suffering tremendously from a want of data.

Acceptance. We want someone to look at us, and really see us—our physical flaws, our personality quirks, our insecurities. And we want them to be okay with every square inch of who we are. We’re always afraid we might be too needy or too much work. We put all these limitations on ourselves and our relationships because we’re afraid that we’re not really loved. That we’re not really accepted. We hide little pieces of ourselves because we think that might be the one thing that finally drives away the person who’s supposed to love us.

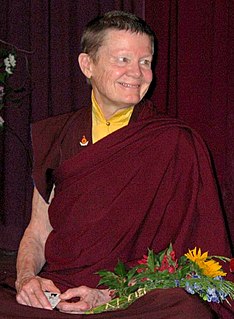

We could learn to stop when the sun goes down and when the sun comes up. We could learn to listen to the wind; we could learn to notice that it's raining or snowing or hailing or calm. We could reconnect with the weather that is ourselves, and we could realize that it's sad. The sadder it is, and the vaster it is, the more our heart opens. We can stop thinking that good practice is when it's smooth and calm, and bad practice is when it's rough and dark. If we can hold it all in our hearts, then we can make a proper cup of tea.

If we begin to get in touch with whatever we feel with some kind of kindness, our protective shells will melt, and we'll find that more areas of our lives are workable. AS we learn to have compassion for ourselves, the circle of compassion for others-what and whom we can work with, and how-becomes wider.

We all have original ideas. Even if we don't see ourselves as supercreative or as wild nonconformists, we have insights every day about how the world around us could be better. It might be a better way of running meetings in your office that would be less mind-numbing. It might be a little twist on a product or a service.

If God seems to be in no hurry to make the problem of evil go away, maybe we shouldn't be, either. Maybe our compulsion to wash God's hands for him is a service he doesn't appreciate. Maybe - all theodicies and nearly all theologians to the contrary - evil is where we meet God. Maybe he isn't bothered by showing up dirty for his dates with creation. Maybe - just maybe - if we ever solved the problem, we'd have talked ourselves out of a lover.

According to a recent study, depression is described as being the disease most destructive to humankind, largely because of the devastation it wreaks on our lives.... Yes, we could set up our minds to ignore our feelings and barricade ourselves from the winds and dust of the brain pattern. And we could become like robots, refusing to consider the passion and joys that could be ours. But then, we also might as well be dead.

In the heroic effort of the handcart pioneers, we learn a great truth. All must pass through a refiner’s fire, and the insignificant and unimportant in our lives can melt away like dross and make our faith bright, intact, and strong. There seems to be a full measure of anguish, sorrow, and often heartbreak for everyone, including those who earnestly seek to do right and be faithful. Yet this is part of the purging to become acquainted with God.

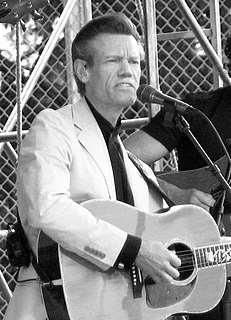

It's always interesting to me when one platform of media crosses into another. We've been on the Terry Gross show Fresh Air a couple of times, and I suddenly felt like we could actually represent ourselves as exactly who we are, in this sort of ultra-vivid way. But the weird thing to me is that the questions she asks are in some ways no different than the questions the guy from the high-school paper asks. She might even ask us where we got our name. But something about it, it's like the pH balance of the trajectory of the questions. Maybe it's just her voice.