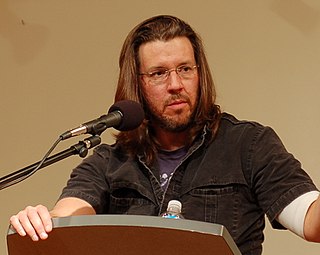

A Quote by Jonathan Dee

Novels are a kind of experiment in selfhood, for the reader as well as for the author.

Related Quotes

I think overtly political novels - those that never transcend or contest their author's conscious intentions and prejudices - are problematic. This is not just true of the innumerable unread books in the socialist realist tradition, but also of novels that carry the burden of conservative ideologies, like Guerrillas, Naipaul's worst book, where the author's disgust for a certain kind of black activist and white liberal is overpowering.

We must be forewarned that only rarely does a text easily lend itself to the reader's curiosity... the reading of a text is a transaction between the reader and the text, which mediates the encounter between the reader and writer. It is a composition between the reader and the writer in which the reader "rewrites" the text making a determined effort not to betray the author's spirit.