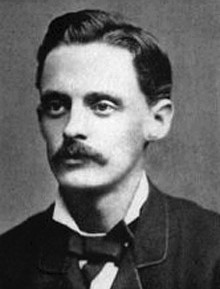

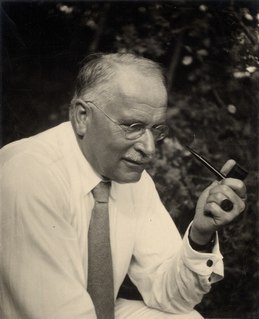

A Quote by Jean Piaget

What the genetic epistemology proposes is discovering the roots of the different varieties of knowledge, since its elementary forms, following to the next levels, including also the scientific knowledge.

Related Quotes

One of the goals of scientific theorising is to develop concepts which are adequate to the phenomena under study. In my view, things should work the same way in epistemology. We want to know what knowledge actually amounts to, not what our folk concept of knowledge is, since, just as with our pretheoretical concept of acidity, it might contain all sorts of misunderstandings and leave out all manner of important things.

The fact that these scientific theories have a fine track record of successful prediction and explanation speaks for itself. (Which is not to say that I don't directly discuss the work of those philosophers who would disagree.) But even if we grant this, many will argue that scientific knowledge in humans, and, indeed, reflective knowledge in general, is quite different in kind from the knowledge we see in other animals.

I see all mythology as one tradition, a way of disseminating knowledge that must come to us in code so that we can live sanely with it, since some forms of knowledge are too dark, or too complex, to be plainly spoken. And so we have these weird (and also sometimes entertaining and surprising and heartening) tales that belong to all of us.

It is easy to see, though it scarcely needs to be pointed out, since it is involved in the fact that Reason is set aside, that faith is not a form of knowledge; for all knowledge is either a knowledge of the eternal, excluding the temporal and historical as indifferent, or it is pure historical knowledge. No knowledge can have for its object the absurdity that the eternal is the historical.

All scientific work is incomplete - whether it be observational or experimental. All scientific work is liable to be upset or modified by advancing knowledge. That does not confer upon us a freedom to ignore the knowledge we already have, to postpone action that it appears to demand at a given time. Who knows, asks Robert Browning, but the world may end tonight? True, but on available evidence most of us make ready to commute on the 8:30 next day.

If the question were, "What ought to be the next objective in science?" my answer would be the teaching of science to the young, so that when the whole population grew up there would be a far more general background of common sense, based on a knowledge of the real meaning of the scientific method of discovering truth.

The principle of science, the definition, almost, is the following: The test of all knowledge is experiment. Experiment is the sole judge of scientific "truth." But what is the source of knowledge? Where do the laws that are to be tested come from? Experiment, itself, helps to produce these laws, in the sense that it gives us hints. But also needed is imagination to create from these hints the great generalizations--to guess at the wonderful, simple, but very strange patterns beneath them all, and then to experiment to check again whether we have made the right guess.