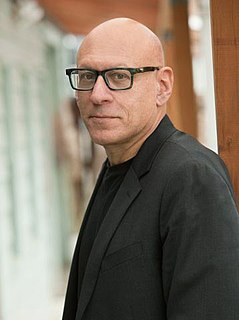

Цитата Кейт Марвин

Поэзия-исповедь, на мой взгляд, более скользкая, чем стихи небрежно-автобиографические; Я нахожу исповедальный стиль гораздо более похожим на драматический монолог.

Связанные цитаты

На самом деле я понятия не имею, какое место я занимаю в поэтических лагерях. На конференциях AWP я участвовал в дискуссиях о юморе, сотрудничестве, визуальной поэзии, исповедальной поэзии, гендере и теле, а также о дань уважения Эдварду Филду и Альберту Голдбарту. На всех них я чувствовал себя как дома — большинство поэтов принадлежат к более чем одной школе.

Конфессионализм относится к цветным писателям. Я думаю, что конфессиональная поэзия в своем роде очень католическая, с большой буквы. Одна из формообразующих идей конфессионализма, выходящая за рамки психоанализа, — это действительное грехопадение. И, по крайней мере, в Америке цветные люди никогда не занимают такого положения благодати, как это делают белые. Так что я думаю, что в некоторых очень реальных отношениях конфессиональная мода, строго говоря, невозможна для небелых писателей.

Поэзия трудна, я имею в виду интересную поэзию, а не конфессиональную болтовню или эмоциональную пропаганду. Чтение нового поэта — это открытие целого мира, того, что Стивенс назвал «мундо», и требуется много времени, чтобы сориентироваться в таком мире. Что мы должны научиться делать тогда, как учителя и активисты поэтического мятежа, так это поощрять людей учиться любить трудности поэзии. Я просто не понимаю большую часть поэзии, которую люблю.