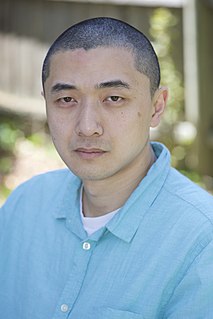

Цитата Кристиана Вимана

Я не думаю, что кто-то, кто не говорит на языке оригинала, может рассчитывать на настоящий перевод.

Темы цитат

Связанные цитаты

В переводоведении мы говорим о доместикации — стилях перевода, которые делают что-то знакомым, или об отчуждении — стилях перевода, которые делают что-то радикально другим. В своем переводе я использую и то, и другое, и модернизм использует и то, и другое. Например, если вы посмотрите на то, как Джеймс Джойс представляет Улисса, станет ли это приручением классикой? Думайте об этом как об эксперименте с хорошо известным текстом на другом языке.

Я недостаточно хорошо владею языками, чтобы давать экспертную оценку написанию в переводе, но, поскольку меня интересует неловкость в прозе, мне нравится, как переведенные тексты иногда могут приобретать несуразность в процессе перевода. Перевод может создать несоответствие, которое, как мне кажется, иногда рассматривается как слабость, но которое, как мне кажется, может быть действительно интересным аспектом текста.