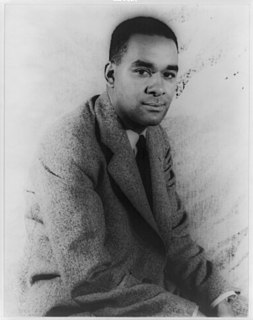

A Quote by Richard Wright

I knew that I lived in a country in which the aspirations of black people were limited, marked-off. Yet I felt that I had to go somewhere and do something to redeem my being alive.

Related Quotes

Some were getting married; some were getting divorced. People were in different places, but you had enough time on this earth to actually get somewhere, and I think that's the exciting thing about being 36 and in your mid-30s. You've been somewhere, and you're going to go somewhere. It's fun; it's exciting.

I was proud, excited and a little frightened. It was all taking off so quickly…the more successful the boys were, the further away from me John felt. I was getting used to being a mum, but most of the time I felt like a single parent…it was hard not to feel frustrated with being stuck at home. I loved Julian, but I knew that if I hadn’t had him I could have seen much more of John and that was hard…I felt shut off from the life he was living. After years at his side, I was excluded, just as it was all happening.

She smiled. She knew she was dying. But it did not matter any longer. She had known something which no human words could ever tell and she knew it now. She had been awaiting it and she felt it, as if it had been, as if she had lived it. Life had been, if only because she had known it could be, and she felt it now as a hymn without sound, deep under the little whole that dripped red drops into the snow, deeper than that from which the red drops came. A moment or an eternity- did it matter? Life, undefeated, existed and could exist. She smiled, her last smile, to so much that had been possible.

Even though I knew I was inside the space shuttle getting ready to go fly, something about it wasn't completely real up until we got the call at about one minute to go, to close and lock our visors and start our oxygen flow. People often ask me, "What did it feel like right at the moment of launch?" And they're surprised when I tell them actually what I felt was relief. It wasn't like being anxious or scared or anything. It was relief because this is something I had wanted to do my whole life and now that the boosters had lit, we were on our way to go do it and nothing was going to stop us.

My mother and my father had very, very strong Scots accents. We were Australian, and in those days when I was young, I spoke with a much more of an Australian accent than I have now. However I knew that if I went to England to become an actor, which I was determined to, I knew that I had to get rid of the Australian accent. We were colonials, we were Down Under somewhere, we were those little people Over There. But I was determined to become an Englishman. So I did.

And I felt more like me than I ever had, as if the years I'd lived so far had formed layers of skin and muscle over myself that others saw as me when the real one had been underneath all along, and I knew writing- even writing badly- had peeled away those layers, and I knew then that if I wanted to stay awake and alive, if I wanted to stay me, I would have to keep writing.

Sometimes I even felt like he dated me as part of his plan, like they were going to have a checklist on the application, and one of the things to tick off was going to be, "Do you have a reasonably intelligent girlfriend who shares your aspirations, and who is fully prepared to accept your limited availability?

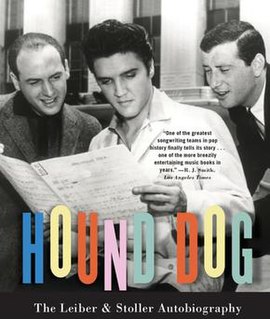

I first became fascinated with the Sears catalogue because all the people in its pages were perfect. Nearly everybody I knew had something missing, a finger cut off, a toe split, an ear half-chewed away, an eye clouded with blindness from a glancing fence staple. And if they didn't have something missing, they were carrying scars from barbed wire, or knives, or fishhooks. But the people in the catalogue had no such hurts. They were not only whole, had all their arms and legs and eyes on their unscarred bodies, but they were also beautiful.