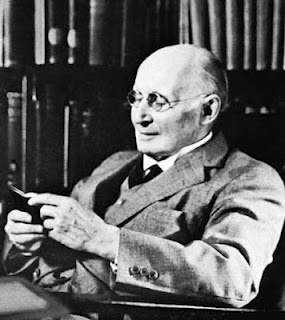

A Quote by Ronald Fisher

The analysis of variance is not a mathematical theorem, but rather a convenient method of arranging the arithmetic.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

I think that if your tenure case depends on your proving what you thought was a mathematical theorem and the proposed theorem turns out to be false just before your tenure decision, and you want to get tenure very badly, there is a sense in which it's perfectly understandable and reasonable of you to wish the proposed theorem were true and provable, even if it's logically impossible for it to be.

If the system exhibits a structure which can be represented by a mathematical equivalent, called a mathematical model, and if the objective can be also so quantified, then some computational method may be evolved for choosing the best schedule of actions among alternatives. Such use of mathematical models is termed mathematical programming.

If you have to prove a theorem, do not rush. First of all, understand fully what the theorem says, try to see clearly what it means. Then check the theorem; it could be false. Examine the consequences, verify as many particular instances as are needed to convince yourself of the truth. When you have satisfied yourself that the theorem is true, you can start proving it.

It seems perfectly clear that Economy, if it is to be a science at all, must be a mathematical science. There exists much prejudice against attempts to introduce the methods and language of mathematics into any branch of the moral sciences. Most persons appear to hold that the physical sciences form the proper sphere of mathematical method, and that the moral sciences demand some other method-I know not what.

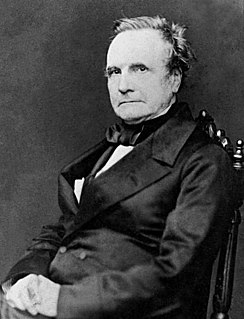

As in Mathematicks, so in Natural Philosophy, the Investigation of difficult Things by the Method of Analysis, ought ever to precede the Method of Composition. This Analysis consists in making Experiments and Observations, and in drawing general Conclusions from them by Induction, and admitting of no Objections against the Conclusions, but such as are taken from Experiments, or other certain Truths. For Hypotheses are not to be regarded in experimental Philosophy.

In fact, Gentlemen, no geometry without arithmetic, no mechanics without geometry... you cannot count upon success, if your mind is not sufficiently exercised on the forms and demonstrations of geometry, on the theories and calculations of arithmetic ... In a word, the theory of proportions is for industrial teaching, what algebra is for the most elevated mathematical teaching.

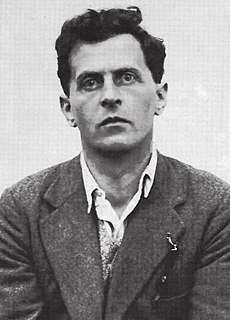

Mathematics is a logical method. . . . Mathematical propositions express no thoughts. In life it is never a mathematical proposition which we need, but we use mathematical propositions only in order to infer from propositions which do not belong to mathematics to others which equally do not belong to mathematics.