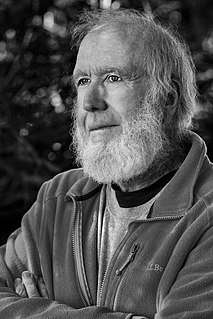

A Quote by Stephen H. Segal

There are plenty of characters of color in fantasy and science fiction. But when you ask the question, "How many of them on-screen have rich, thought-out backgrounds and family elements to draw on?," you quickly find out that the answer is not very many.

Related Quotes

If you thought you were trying to find out more about it because you're gonna get an answer to some deep philosophical question...you may be wrong! It may be that you can't get an answer to that particular question by finding out more about the character of nature. But my interest in science is to simply find out about the world.

'Who are we?' And to me that's the essential question that's always been in science fiction. A lot of science fiction stories are - at their very best - evocations of that question. When we look up at the night sky and wonder, 'Is there anyone else out there?' we're also asking who we are we in relation to them.

Who are we? And to me that's the essential question that's always been in science fiction. A lot of science fiction stories are - at their very best - evocations of that question. When we look up at the night sky and wonder, "Is there anyone else out there?" we're also asking who we are we in relation to them.

I'm a self trained, autodidactic artist, so all I was ever trying to do was to draw as realistically as possible - but that's what comes out, because I don't really know how to draw! I think when I draw characters, I'm able to reduce them down to little marks that capture the most distinct elements of them.

Science fiction is fantasy about issues of science. Science fiction is a subset of fantasy. Fantasy predated it by several millennia. The '30s to the '50s were the golden age of science fiction - this was because, to a large degree, it was at this point that technology and science had exposed its potential without revealing the limitations.

Of course, to avoid getting stuck in that convo with someone you dislike or feel uncomfortable around, don't be passive, be proactive. Do not let them direct your interaction on their terms, do it on yours. Ask a Misdirection Question--something too difficult to answer quickly--e.g., 'What's Congress up to?' or 'You ever learn any cool science?' When you ask the question, don't make eye contact, keep moving and get out of there. Do not wait for a response and deny ever asking it. Repeat these actions until you are never again spoken to by that individual (about four times).

But in the end, science does not provide the answers most of us require. Its story of our origins and of our end is, to say the least, unsatisfactory. To the question, "How did it all begin?", science answers, "Probably by an accident." To the question, "How will it all end?", science answers, "Probably by an accident." And to many people, the accidental life is not worth living. Moreover, the science-god has no answer to the question, "Why are we here?" and, to the question, "What moral instructions do you give us?", the science-god maintains silence.

When the wrong question is being asked, it usually turns out to be because the right question is too difficult. Scientists ask questions they can answer. That is, it is often the case that the operations of a science are not a consequence of the problematic of that science, but that the problematic is induced by the available means.

I define science fiction as the art of the possible. Fantasy is the art of the impossible. Science fiction, again, is the history of ideas, and they're always ideas that work themselves out and become real and happen in the world. And fantasy comes along and says, 'We're going to break all the laws of physics.' ... Most people don't realize it, but the series of films which have made more money than any other series of films in the history of the universe is the James Bond series. They're all science fiction, too - romantic, adventurous, frivolous, fantastic science fiction!