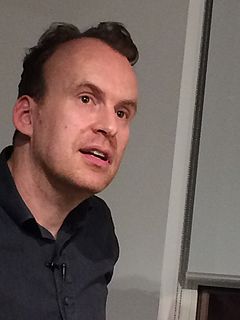

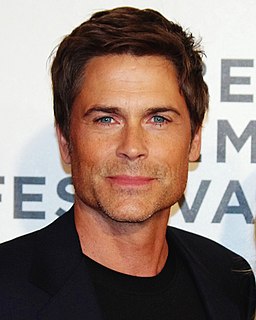

A Quote by William Mapother

I can be a bit of a science geek. I tend more towards reading about brain science, neuroscience.

Related Quotes

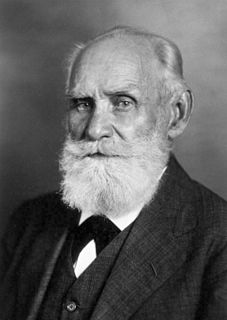

One can truly say that the irresistible progress of natural science since the time of Galileo has made its first halt before the study of the higher parts of the brain, the organ of the most complicated relations of the animal to the external world. And it seems, and not without reason, that now is the really critical moment for natural science; for the brain, in its highest complexity-the human brain-which created and creates natural science, itself becomes the object of this science.

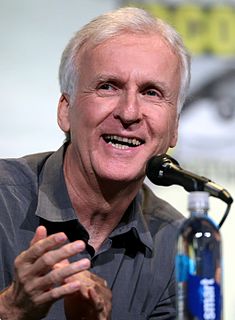

Literary science fiction is a very, very narrow band of the publishing business. I love science fiction in more of a pop-culture sense. And by the way, the line between science fiction and reality has blurred a lot in my life doing deep ocean expeditions and working on actual space projects and so on. So I tend to be more fascinated by the reality of the science-fiction world in which we live.