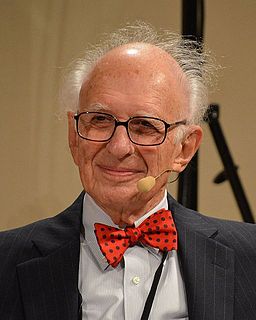

A Quote by Eric Kandel

There was little in my early life to indicate that an interest in biology would become the passion of my academic career. In fact, there was little to suggest I would have an academic career.

Related Quotes

I began to read [Bible] as a critic, an in-house critic. So I got to a place where when I got to the university, I just couldn't reconcile that book and some of its points of view with stuff I was learning in my academic career. And so then you have a choice: either you give up your academic career and close your mind and become a constant fundamentalist, or you give up your religion and become a citizen of the modern world and get a modern education, or just spend the rest of your life balancing the two things together, forcing them into a dialogue.

There's actually a wonderful quote from Stanley Fish, who is sometimes very polemical and with whom I don't always agree. He writes, "Freedom of speech is not an academic value. Accuracy of speech is an academic value; completeness of speech is an academic value; relevance of speech is an academic value. Each of these is directly related to the goal of academic inquiry: getting a matter of fact right."

I decided to become a teacher because I thought it would be a great career where I could wear different hats. You're an academic one moment, and you're a psychologist the next moment, an athlete the next moment... when you are out on the playground or coaching...so it enables you to play different roles.

I drifted into a career in academic philosophy because I couldn't see anything outside the academy that looked to be anything other than drudgery. But I wouldn't say I 'became a philosopher' until an early mid-life crisis forced me to confront the fact that, while 'philosophy' means 'love of wisdom', and 'wisdom' is the knowledge of how to live well, the analytic philosophy in which I had been trained seemed to have nothing to do with life.