Top 60 Beirut Quotes & Sayings

Explore popular Beirut quotes.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

When I arrived in Beirut from Europe, I felt the oppressive, damp heat, saw the unkempt palm trees and smelt the Arabic coffee, the fruit stalls and the over-spiced meat. It was the beginning of the Orient. And when I flew back to Beirut from Iran, I could pick up the British papers, ask for a gin and tonic at any bar, choose a French, Italian, or German restaurant for dinner. It was the beginning of the West. All things to all people, the Lebanese rarely questioned their own identity.

There is a single theme behind all our work-we must reduce population levels. Either governments do it our way, through nice clean methods, or they will get the kinds of mess that we have in El Salvador, or in Iran or in Beirut. Population is a political problem. Once population is out of control, it requires authoritarian government, even fascism, to reduce it.

Outside events can change a presidential campaign, a president, and the history of the nation: the Iranian hostage crisis, the bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut, the downing of the helicopter in Mogadishu, Somalia, the suicide attack on the USS Cole, and, of course, the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

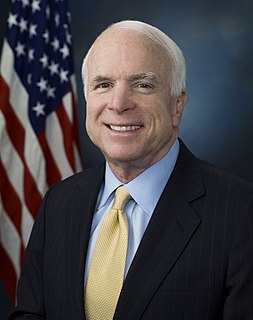

I have had a strong and a long relationship on national security, I've been involved in every national crisis that this nation has faced since Beirut, I understand the issues, I understand and appreciate the enormity of the challenge we face from radical Islamic extremism. I am prepared. I am prepared. I need no on-the-job training. I wasn't a mayor for a short period of time. I wasn't a governor for a short period of time.

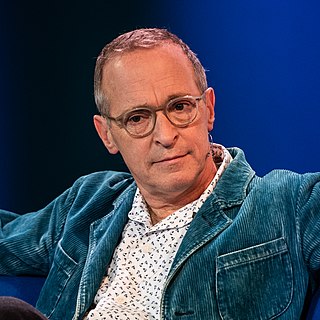

I'd known the people at Rolling Stone for a while. I'd gone to them with a piece I'd done on Beirut for Vanity Fair that Vanity Fair didn't want to publish, because they said I was making fun of death... This was Tina Brown.But they paid me for it. So I've got this big chunk of a piece, and Rolling Stone liked it, but they thought it was a little dated. But then they called me back and asked me to do a similar piece about the Turks and Caicos Islands, where the whole government had been arrested for dope smuggling. That was fun.

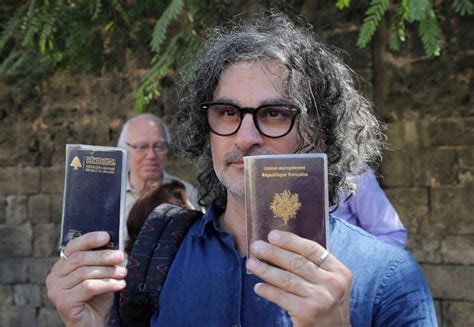

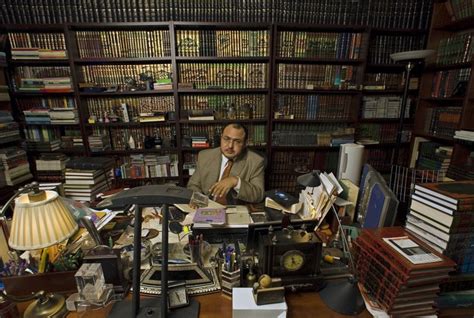

I need to have one foot inside and one foot outside a culture to be able to write about it. For example, I couldn't write about the gay culture if I were wholly inside or outside of it. Finding that distance is always interesting. I jokingly say that when I'm in America, I write about Beirut, and when I'm in Beirut, I write about America. A lot of my friends in Beirut think I'm more American than Lebanese. Here, my friends think of me more as Lebanese.

Many of Islam's apologists insist that suicide bombing is not Islamic because the Koran forbids suicide. Mmm-hmm. So where are all the Muslims gathering in mass demonstrations to vehemently condemn this practice that slanders their religion? Why does contemporary Islam promote 'martyrdom' as the highest duty of Muslims? Why are photographs of suicide bombers plastered everywhere in Beirut? Because Islam is what Islam does.

For my generation - the "Children of Nixon," as I call us in the book - the Lebanese civil war was an iconic event. Downtown Beirut became a metaphor for so many things: man's inhumanity to man, what Charles Bukowski called "the impossibility of being human." It shaped our perceptions of war and human nature, just as Vietnam did for our parents. We used it to understand how the world works.

In 1982, Israel began an invasion across its northern border, seeking to root out elements of the Palestine Liberation Organization. The Israeli military wreaked destruction all the way up to Beirut and forced the P.L.O. out of Lebanon. It also defeated the Syrian Army and, particularly, the Air Force wherever it engaged them.

For me, diversity is not a value. Diversity is what you find in Northern Ireland. Diversity is Beirut. Diversity is brother killing brother. Where diversity is shared - where I share with you my difference - that can be valuable. But the simple fact that we are unlike each other is a terrifying notion. I have often found myself in foreign settings where I became suddenly aware that I was not like the people around me. That, to me, is not a pleasant discovery.

The first suicide bombing that entered my consciousness was the Beirut embassy bombing. It was very personal. I'd been in the embassy and I knew most of the people in the station who were killed in the bombing. So you take the personal aspect of it and the mystery of who the bomber was and the fact that a small group of people could drive us out of a country that was absolutely key to the United States, and what was behind this... The fact that they've been able to hide the embassy bombers' identities for all these years tells me we're up against a very capable movement.

People in the United States don't like to hear it, but puritanical Islam has been on the rise because of our unequivocal policy of absolute support for Israel, regardless of what Israel does - even if they invade Lebanon and bombard a major city like Beirut, full of civilians. Israel has atomic bombs, but we go nuts if any Arab country or Iran develops even nuclear capabilities.

It was important for me to show that Beirut and Lebanon were once the pearl of the Middle East. Beirut was once called the Paris of the Middle East and to have that feeling of a destroyed place that once was beautiful and glamorous and visually impressive was important. I think it's even sadder to get the feeling that this country, and indeed the whole Middle East, could have been a major force in the world if people would get together and forget about destruction, death and wars. But unfortunately, it's not happening yet.

For Beirut it was the civil war, and the dividing of the city - which is something that is shared among Beirut, Berlin and Baghdad. And Cairo is a city that has a scar that was born after many decades of dictatorship - oppression shaped the people's lives, and forced people to grow up accompanied by fear. I belong to a generation that, whether we like it or not, was shaped by this fear of death or loosing the people you love, the threat of war, not allowed to be yourself, forced to be silent - as you watch ignorance occupying everything around you. And this is a deep scar.

Lebanon was at one time known as a nation that rose above sectarian hatred; Beirut was known as the Paris of the Middle East. All of that was blown apart by senseless religious wars, financed and exploited in part by those who sought power and wealth. If women had been in charge, would they have been more sensible? It's a theory.

I'd spent thirty years visiting the Dalai Lama, and twenty years as a journalist going to difficult places, war zones and revolutions from North Korea to Haiti and Beirut to Sri Lanka, and the question came up: What does this man have to offer to this world which seems so torn up and so attached to conflict?

After the allied victory of 1918, at the end of my father's war, the victors divided up the lands of their former enemies. In the space of just seventeen months, they created the borders of Northern Ireland, Yugoslavia and most of the Middle East. And I have spent my entire career — in Belfast and Sarajevo, in Beirut and Baghdad — watching the people within those borders burn.

As I searched the atlas for somewhere to run to, Hugh made a case for his old stomping grounds. His first suggestion was Beirut, where he went to nursery school. His family left there in the midsixties and moved to the Congo. After that, it was Ethiopia, and then Somalia, all fine places in his opinion. 'Let's save Africa and the Middle East for when I decide to quit living,' I said.

My memories of Kabul are vastly different than the way it is when I go there now. My memories are of the final years before everything changed. When I grew up in Kabul, it couldn't be mistaken for Beirut or Tehran, as it was still in a country that's essentially religious and conservative, but it was suprisingly progressive and liberal.