Top 47 Borges Quotes & Sayings

Explore popular Borges quotes.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

I remember I was very taken with a book called DreamTigers by [Jorge Luis] Borges. He was at the University of Texas, Austin, and they collected some of his writings and put them in a little collection. It's called DreamTigers in English, but it doesn't exist in Spanish. It's a little sampler. But that collection in English is what struck me, because in there he has his poems, and I was a poet as well as a fiction writer.

Jorge Luis Borges wrote a poem when he was in his 80s about one day writing the book that would justify him. This was long after he had become one of the great masters, a writer everyone looks up to and reveres. As artists, I don't think we ever see ourselves as done. We always think we're at the beginning . . .

I really wouldn't call a lot of what's online "literature" since that word, to me, refers to a sub-genre of writing that belongs to the heavy-hitters, the canonical writers, Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Dostoevsky, Kafka, and even Toni Morrison, George Saunders, Thomas Bernhard, Sebald, Borges, DFW, e.g.

There [DreamTigers by Jorge Luis Borges] were these little fablesque things, you know, dream tigers, beautiful, beautiful pieces that when you read them had the power of a long piece, but they were prose, and they had the power of poetry, in that the last line wasn't the end, it was a reverberation, like when you tap on a glass made of crystal, and it goes ping.

I'm educating myself more about world poetry. I know a lot about contemporary American poetry, so I felt I needed to learn more about figures like Borges, Akhmatova, Neruda, etc. I felt I needed a bigger lens to see poetry through. It really helps to see poetry as a world language, and not just something American.

I have for a long time loved fabulist, imaginative fiction, such as the writing of Italo Calvino, Jose Saramago, Michael Bulgakov, and Salman Rushdie. I also like the magic realist writers, such as Borges and Marquez, and feel that interesting truths can be learned about our world by exploring highly distorted worlds.

Jorge Luis Borges had the soapbox and the authority to complain about this myopic understanding of the duty of Latin American writers, which sometimes forecloses their unique modernism and experience of modernization in favor of a mythic past or an artificially constructed ideal national subject. So likewise in João Gilberto Noll, readers shouldn't expect samba and Carnival and football. The Brazilian national identity is not one of his primary concerns.

Jorge Luis Borges was lamenting a variety of Orientalism that was used to measure the alleged authenticity of Argentine and Latin American writers in the midcentury. The Argentine literary tradition was believed by many, including many Argentines, to be concerned with a national imaginary in which the gauchos and the pampas and the tango were fundamental tropes. Borges, in part to legitimize his own Europhilia, correctly pointed out that expecting writers to engage with these romantic nationalist tropes was arbitrary and limiting, a genre that was demonstrative of its own artificiality.

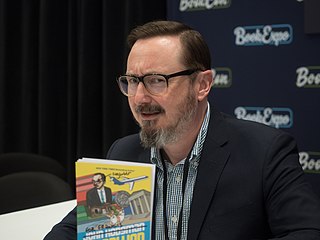

Nazi Literature in the Americas, a wicked invented encyclopedia of imaginary fascist writers and literary tastemakers, is Bolaño playing with sharp, twisting knives. As if he were Borges's wisecracking, sardonic son, Bolaño has meticulously created a tightly woven network of far-right litterateurs and purveyors of belles lettres for whom Hitler was beauty, truth, and the great lost hope.

From Borges, those wonderful gaucho stories from which I learned that you can be specific as to a time and place and culture and still have the work resonate with the universal themes of love, honor, duty, betrayal, etc. From Amiri Baraka, I learned that all art is political, although I don't write political plays.

I always read the Latin American writers. I love so many of them: Gabriel García Márquez, José Donoso, Alejo Carpentier, Jorge Luis Borges, Clarice Lispector. I also love a lot of American experimental writers and surrealist European writers. But perhaps The Persian Book of Kings was the greatest influence - I encourage people to look at it. There is such a wealth of incredible stories.

I was an eccentric teenager in suburban New Jersey, in a town mostly interested in sports, popularity, and clothes. A fan of Jorge Luis Borges, I found a group of Borges scholars from Aarhus, Denmark - perfect strangers - whom I connected to online and immediately became enthralled by the idea of virtual communities.

He is no true reader who has not experienced the reproachful fascination of the great shelves of unread books, of the libraries at night of which Borges is the fabulist. He is no reader who has not heard, in his inward ear, the call of the hundreds of thousands, of the millions of volumes which stand in the stacks of the British Library asking to be read. For there is in each book a gamble against oblivion, a wager against silence, which can be won only when the book is opened again (but in contrast to man, the book can wait centuries for the hazard of resurrection.)

The Anglo-American tradition is much more linear than the European tradition. If you think about writers like Borges, Calvino, Perec or Marquez, they're not bound in the same sort of way. They don't come out of the classic 19th-century novel, which is where all the problems start. 19th-century novels are fabulous and we should all read them, but we shouldn't write them.

I am sometimes asked to name my favourite books. The list changes, depending on my mood, the year, tricks played by memory. I might mention novels by Nabokov and Calvino and Tolkien on one occasion, by Fitzgerald and Baldwin and E.B. White on another. Camus often features, as do Tolstoy, Borges, Morrison and Manto.

This is how space begins, with words only, signs traced on the blank page. To describe space: to name it, to trace it, like those portolano-makers who saturated the coastlines with the names of harbours, the names of capes, the names of inlets, until in the end the land was only separated from the sea by a continuous ribbon of text. Is the aleph, that place in Borges from which the entire world is visible simultaneously, anything other than an alphabet?

To think, analyze and invent, he [Pierre Menard] also wrote me, “are not anomalous acts, but the normal respiration of the intelligence. To glorify the occasional fulfillment of this function, to treasure ancient thoughts of others, to remember with incredulous amazement that the doctor universal is thought, is to confess our languor or barbarism. Every man should be capable of all ideas, and I believe that in the future he will be." (Jorge Luis Borges, "Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote, 1939)

When I use a name or place, I want to leave the reader open to the waterfall of determinacy that it may provoke. And I don't know, but I must mention the name Borges. I try to mention it in every one of my works. It's a mark, a stamp, a sort of homage to Argentinidad. But it's an homage that works through pat phrases, those stock images that populate his work: the night, labyrinths, libraries. That is, I don't want simply to pay homage to Borges, but rather the contrary: to recall his commonplaces.

I think Jorge Borges said that when Argentineans die they turn into angels and go and live in Uruguay. But for the rest of South America, you have to say that it's getting there - becoming civilized - and will get there. It's had a real grit war in history. The choice between those societies until recently was the choice between tyranny and chaos. Everyone understood that. You've got to have a strong man, or it's going to be a mess.

I first got online in the late '80s when I was an eccentric teenager in suburban New Jersey, in a town mostly interested in sports, popularity, and clothes. I was a reader, into Jorge Luis Borges, and I found, connected to, and delighted in a group of Borges scholars from Aarhus, Denmark, that I met online.

We have inhabited both the actual and the imaginary realms for a long time. But we don't live in either place the way our parents or ancestors did. Enchantment alters with age, and with the age. We know a dozen Arthurs now, all of them true. The Shire changed irrevocably even in Bilbo's lifetime. Don Quixote went riding out to Argentina and met Jorge Luis Borges there. Plus c'est la même chose, plus ça change.