Top 1200 Death Poems Quotes & Sayings - Page 3

Explore popular Death Poems quotes.

Last updated on April 18, 2025.

When Emily Dickinson's poems were published in the 1890s, they were a best-seller; the first book of her poems went through eleven editions of a print run of about 400. So the first print run out of Boston for a first book of poems was 400 for a country that had fifty million people in it. Now a first print run for a first book is maybe 2,000? So that's a five-time increase in the expectation of readership. Probably the audience is almost exactly the same size as it was in 1900, if you just took that one example.

As a guiding principle I believe that every poem must be its own sole freshly created universe, and therefore have no belief n 'tradition' or a common myth-kitty or casual allusions in poems to other poems or poets, which last I find unpleasantly like the talk of literary understrappers letting you see they know the right people.

I love to read long books. I enjoy experiencing that extension. But it's not something I feel comfortable with and not something I think I can gain comfort with by practice. It was a real struggle for me while writing memoir to get past three pages or so. In poems, I can write long poems. But length in prose: no.

Laughter. Yes, laughter is the Zen attitude towards death and towards life too, because life and death are not separate. Whatsoever is your attitude towards life will be your attitude towards death, because death comes as the ultimate flowering of life. Life exists for death. Life exists through death. Without death there will be no life at all. Death is not the end but the culmination, the crescendo. Death is not the enemy it is the friend. It makes life possible.

I know that one of the things that I really did to push myself was to write more formal poems, so I could feel like I was more of a master of language than I had been before. That was challenging and gratifying in so many ways. Then with these new poems, I've gone back to free verse, because it would be easy to paint myself into a corner with form. I saw myself becoming more opaque with the formal poems than I wanted to be. It took me a long time to work back into free verse again. That was a challenge in itself. You're always having to push yourself.

Precise, graceful, and generous, the poems in SuperLoop, seem to be born out of a deep, careful attention and a profound compassion. Sometimes the quiet observer, sometimes the kid in the center of the messed-up carnival, these poems are the fireflies you’ve missed all winter, the longed-for return of the bees. Unaffected and inherently hopeful, Callihan’s work is as merciful as it is moving.

'Hard Hit,' a YA collection of poems, explores the country of grief and survival. Mark, a 16-year-old boy and skilled pitcher, must confront the coming death of his beloved father with the help of his friends, family, baseball, and an idiosyncratic belief in God. I used my own experience of my parents' deaths to inform this journey.

We are left with nothing but death, the irreducible fact of our own mortality. Death after a long illness we can accept with resignation. Even accidental death we can ascribe to fate. But for a man to die of no apparent cause, for a man to die simply because he is a man, brings us so close to the invisible boundary between life and death that we no longer know which side we are on. Life becomes death, and it is as if this death has owned this life all along. Death without warning. Which is to say: life stops. And it can stop at any moment.

If we will admit time into our thoughts at all, the mythologies, those vestiges of ancient poems, wrecks of poems, so to speak, the world's inheritance,... these are the materials and hints for a history of the rise and progress of the race; how, from the condition of ants, it arrived at the condition of men, and arts were gradually invented. Let a thousand surmises shed some light on this story.

A poem is like a person. The more you know someone, the more you realize there is always something more to know and understand. A final understanding could probably only begin upon permanent separation, or death. This is why we come back to certain poems, as we do to places or people, to experience and re-experience, to see ourselves for who we truly are, and to continue to be changed.

[There are, in us] possibilities that take our breath away, and show a world wider than either physics or philistine ethics can imagine. Here is a world in which all is well, in spite of certain forms of death, death of hope, death of strength, death of responsibility, of fear and wrong, death of everything that paganism, naturalism and legalism pin their trust on.

Poems On Life: Life is given to us, we earn it by giving it. Let the dead have the immortality of fame, but the living the immortality of love. Life's errors cry for the merciful beauty that can modulate their isolation into a harmony with the whole. Life, like a child, laughs, shaking its rattle of death as it runs.

... woman is frequently praised as the more "creative" sex. She does not need to make poems, it is argued; she has no drive to make poems, because she is privileged to make babies. A pregnancy is as fulfilling as, say, Yeats' Sailing to Byzantium.... To call a child a poem may be a pretty metaphor, but it is a slur on the labor of art.

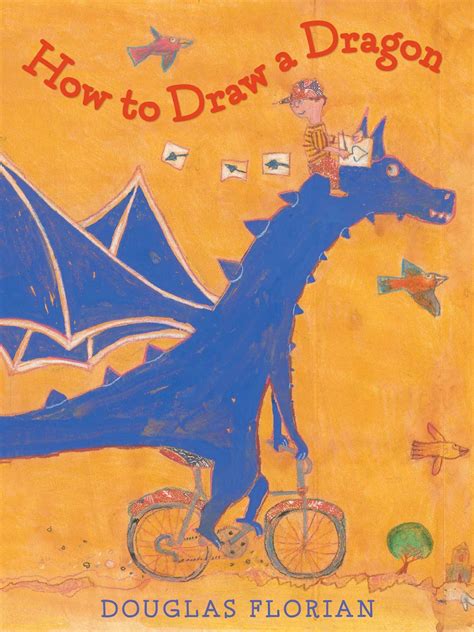

Narrative nonfiction was not my forte. I always wanted to let my imagination run free, and the facts sometimes got in the way. At one point I wanted to illustrate Jack Prelutsky's enchanting poems. Unable to do that, I started devising and improvising my own poems, very raw at first. I immersed myself in verse, writing reams of stuff until it gelled.

The poems in Helena Mesa’s virtuosic first book, Horse Dance Underwater, run with such speed, verve, and alacrity they leave you breathless, exhilarated, and transformed as if the purest kind of song had lifted you into the air. By this quickness of language finding lyric speech, Mesa’s poems remind us of art’s joyous and ecstatic effects.

Some of Mr. Gregory's poems have merely appeared in The New Yorker ; others are New Yorker poems: the inclusive topicality, the informed and casual smartness, the flat fashionable irony, meaningless because it proceeds from a frame of reference whose amorphous superiority is the most definite thing about it they are the trademark not simply of a magazine but of a class.

The judges who awarded the 1980 Commonwealth Poetry Prize to my first collection of poems, Crossing the Peninsula and Other Poems, cited with approval and with no apparent conscious irony my early poem, "No Alarms." The poem was composed probably sometime in 1974 or 1975, and it complained about the impossibility of writing poetry - of being a poet - under the conditions in which I was living then.

Life rises out of death, death rises out of life; in being opposite they yearn to each other, they give birth to each other and are forever reborn. And with them, all is reborn, the flower of the apple tree, the light of the stars. In life is death. In death is rebirth. What then is life without death? Life unchanging, everlasting, eternal?-What is it but death-death without rebirth?

'Love, Death and the Changing of the Seasons' is a kind of novel in verse about the arc of an urban lesbian love affair - and I suppose there is a certain amount of voyeurism in the consumption of fiction! The 'Sancerre' poems here are more contemplative and about the relationship of the individual to local and wider histories.

That being said, some of my favorite poets are extremely funny. The aforementioned Matt Rohrer, for instance. Mary Ruefle. James Tate might be the best example of someone who is systematically misread because he can be hilarious. In his poems, as in all great funny poems, the humor is one very appealing version of the surprise and associative movement that is at the heart of all poetry.

I wrote two poems about the 81 uprisings: Di Great Insohreckshan and Mekin Histri. I wrote those two poems from the perspective of those who had taken part in the Brixton riots. The tone of the poem is celebratory because I wanted to capture the mood of exhilaration felt by black people at the time.

I wrote two poems about the '81 uprisings: 'Di Great Insohreckshan' and 'Mekin Histri.' I wrote those two poems from the perspective of those who had taken part in the Brixton riots. The tone of the poem is celebratory because I wanted to capture the mood of exhilaration felt by black people at the time.

As deaths have accumulated I have begun to think of life and death as a set of balance scales. When one is young, the scale is heavily tipped toward the living. With the first death, the first consciousness of death, the counter scale begins to fall. Death by death, the scales shift weight until what was unthinkable becomes merely a matter of gravity and the fall into death becomes an easy step.

We tend to suffer from the illusion that we are capable of dying for a belief or theory. What Hagakure is insisting is that even in merciless death, a futile death that knows neither flower nor fruit has dignity as the death of a human being. If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.

I wrote the poems in Charms Against Lightning one by one, over almost a decade, and I did not write them toward any theme or narrative. But once I really got serious about putting together a book, I began to see that in fact there were themes across the poems, if only because my own obsessions had brought me back time and again to the same ground. I realized that any ordering of the poems would determine how those themes developed over the manuscript, and how the collection's dramatic conflicts were resolved.

By 'coming to terms with life' I mean: the reality of death has become a definite part of my life; my life has, so to speak, been extended by death, by my looking death in the eye and accepting it, by accepting destruction as part of life and no longer wasting my energies on fear of death or the refusal to acknowledge its inevitability. It sounds paradoxical: by excluding death from our life we cannot live a full life, and by admitting death into our life we enlarge and enrich it.