Top 1200 Reader's Digest Quotes & Sayings

Explore popular Reader's Digest quotes.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

I'm doing a lot of cognitive processing. I'm gathering research. I'm processing it. I'm arranging the data. I'm sorting out the narrative. I'm designing. It's almost as if I do all the cognitive work that you then don't have to do. I digest it, process it, and then offer something that's very easy for you to digest.

Nice writing isn't enough. It isn't enough to have smooth and pretty language. You have to surprise the reader frequently, you can't just be nice all the time. Provoke the reader. Astonish the reader. Writing that has no surprises is as bland as oatmeal. Surprise the reader with the unexpected verb or adjective. Use one startling adjective per page.

We must be forewarned that only rarely does a text easily lend itself to the reader's curiosity... the reading of a text is a transaction between the reader and the text, which mediates the encounter between the reader and writer. It is a composition between the reader and the writer in which the reader "rewrites" the text making a determined effort not to betray the author's spirit.

Explaining is a difficult art. You can explain something so that your reader understands the words; and you can explain something so that the reader feels it in the marrow of his bones. To do the latter, it sometimes isn't enough to lay the evidence before the reader in a dispassionate way. You have to become an advocate and use the tricks of the advocate's trade.

Every reader, as he reads, is actually the reader of himself. The writer's work is only a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he might never have seen in himself without this book. The reader's recognition in himself of what the book says is the proof of the book's truth.

The first rule is you have to create a reality that makes the reader want to come back and see what happens next. The way I tried to do it, I'd create characters that the reader could instantly recognize, and hopefully bond with, and put them through situations that keep the reader on the edge of their seat.

The poem is not, as someone put it, deflective of entry. But the real question is, 'What happens to the reader once he or she gets inside the poem?' That's the real question for me, is getting the reader into the poem and then taking the reader somewhere, because I think of poetry as a kind of form of travel writing.

By clarity I don't mean that we're always in kind of a simple area where everything is clear and comforting and understood. Clarity is certainly a way toward disorientation because if you don't start out - if the reader isn't grounded, if the reader is disoriented in the beginning of the poem, then the reader can't be led astray or disoriented later.

...we're told by TV and Reader's Digest that a crisis will trigger massive personal change--and that those big changes will make the pain worthwhile. But from what he could see, big change almost never happens. People simply feel lost. They have no idea what to say or do or feel or think. they become messes and tend to remain messes.

In my couple of books, including Going Clear, the book about Scientology, I thought it seemed appropriate at the end of the book to help the reader frame things. Because we've gone through the history, and there's likely conflictual feelings in the reader's mind. The reader may not agree with me, but I don't try to influence the reader's judgment. I know everybody who picks this book up already has a decided opinion. But my goal is to open the reader's mind a little bit to alternative narratives.

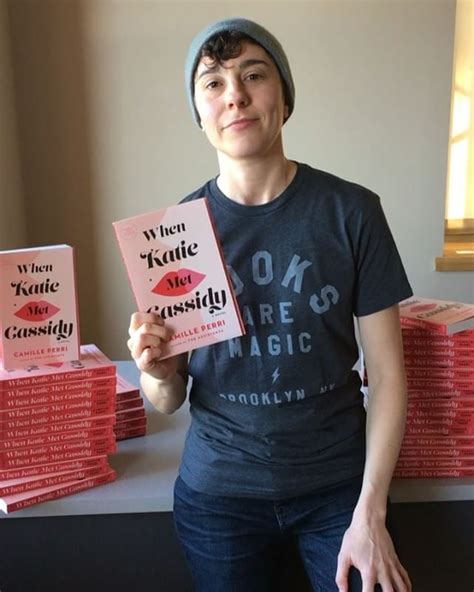

The book is finished by the reader. A good novel should invite the reader in and let the reader participate in the creative experience and bring their own life experiences to it, interpret with their own individual life experiences. Every reader gets something different from a book and every reader, in a sense, completes it in a different way.