Top 130 Rwanda Quotes & Sayings - Page 2

Explore popular Rwanda quotes.

Last updated on April 16, 2025.

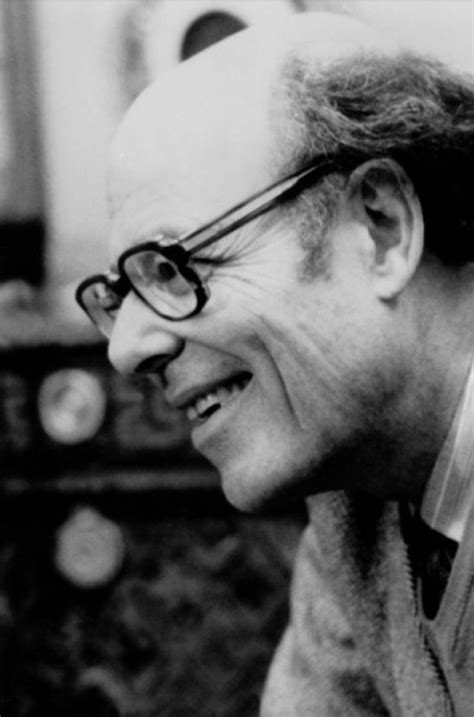

One of the things I write about a bit in my Madam Secretary memoir is on Rwanda, where I was an instructed ambassador at the U.N., and my instructions were to not vote for increased forces there, and I didn't like my instructions. So I got up and called Washington and said, "Change my instructions," and they didn't.

Post-genocide Rwanda has managed to implement a good universal health insurance scheme that covers a large proportion of the population. This came about because of the severity of the country's problems and the resulting high proportion of women in the parliament and among professional caregivers, which had a positive effect on policy.

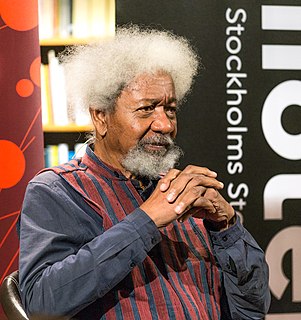

The West has institutions that can punish the misconduct of individuals. What drove Rwanda and Africa into decline was the fact that certain people weren't held accountable. When we move to make corrupt mayors or officers answer to the courts, people always immediately say that we are repressive. But should we allow these people to continue to get away with it?

Genocide, in my opinion - is an attempt by a powerful group completely to eradicate from the face of the Earth the existence of people because of their ethnic makeup or because of their race or religion, and that was the case with Hitler trying to exterminate the Jews, and that was the case in Rwanda, when the Tutsis were attacked and over 500,000 were killed in two or three days.

We do not have a South African as a member of the African Commission. The President of the Commission comes from Mali, the Deputy comes from Rwanda and then we have got all these other members, ordinary commissioners. There is no South African there. And the reason, again, for that is not because we didn't have South Africans who are competent.

In Rwanda, we have a society that has experienced a very serious rupture and you can't expect all of a sudden that things will be perfect. Even so: You cannot find any more areas where any segment of the population would be afraid to go, like we used to have before. But there is always a lot more to do.

The great gift of 'Incarceration Nations' is that, by introducing a wide range of approaches to crime, punishment, and questions of justice in diverse countries - Rwanda, South Africa, Brazil, Jamaica, Uganda, Singapore, Australia and Norway - it forces us to face the reality that American-style punishment has been chosen.

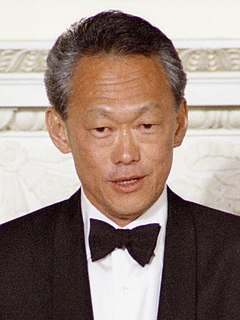

You’re talking about Rwanda or Bangladesh, or Cambodia, or the Philippines. They’ve got democracy, according to Freedom House. But have you got a civilised life to lead? People want economic development first and foremost. The leaders may talk something else. You take a poll of any people. What is it they want? The right to write an editorial as you like? They want homes, medicine, jobs, schools.

I know that the fact that I am candidate to my own succession in 2017 can be perceived to be a bad thing by some part of the public opinion outside Rwanda and I don't mind because I know that I am doing it for a good cause. It really doesn't matter to me that my name is associated to those critics as long as I know that I am doing the will of the people.

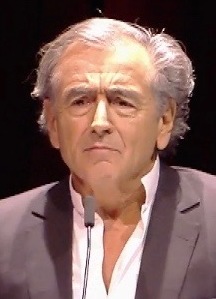

Each time a Palestinian or an Israeli dies, it is terrible. But they have the right to have a funeral, to be buried, to have a place in the memory of the survivors. And then you have these other places - Darfur, Rwanda, even Colombia - where the dead have no faces and literally cannot be counted. Theirs are minuscule lives moving toward imperceptible deaths. For me, it is the essence of tragedy.

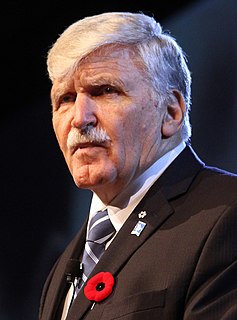

I felt it absolutely essential that we plant the U.N. flag in Rwanda and plant it in a place of significance to show all the political entities, all the signees of the agreement and the Rwandans... that the international community were here and we're here to stay and we're going to be doing our job.

When I won the Oscar, I fell into that mind-set that this is a precious role. People everywhere were shouting, 'Show me the money!' I just didn't want anything that could parody the fact that I was like a tagline in a movie. So when Steven Spielberg offered me 'Amistad,' I said no; when 'Hotel Rwanda' came along, I said no.

I went to Rwanda with my wife who had been going for the past three summers. She is an art therapist who works with survivors of the genocide. I decided to become a volunteer also, and to teach filmmaking. But thinking about how to approach a class, it made sense to start making a movie there, with the kids.

The beautiful faces of the children I’ve met in Rwanda and in other countries are with me every day and fuel my passion to raise awareness of the global hunger issue. That’s why I’m urging everyone to join me and #PassTheRedCup for Yum! Brands’ World Hunger Relief effort. Together we can move millions of children from hunger to hope.

I am not responsible for creating an opposition, neither am I responsible for appointing my own successor. My job is to allow for the opposition to exist within what the realms of the law. There is space in Rwanda for political parties - if fact we have about a dozen of them - as long as their objective is not to take us back twenty two years. On that point, we are and will always be very vigilant.

One of my fondest memories growing up in Rwanda was seeing everyone participating in community-building activities. This happened every Saturday at the end of month. People work together in cleaning streets, planting trees, and take care of each other by facilitating productive conversations and actions that are beneficial for the society.

If there is any hope that we in America might one day overcome our own history of genocide, slavery, discrimination, and oppression and create a justice system that is truly a source of international pride rather than shame, I suspect Rwanda may have as much to teach us about what is required as any tour of a Norwegian prison.

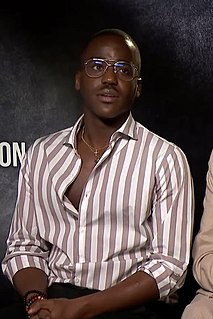

I'd been warned that acting was an unstable profession and knew my parents couldn't support me financially. I had assured them I was going to work as hard as possible to make this career happen so their hard work, as immigrants who fled Rwanda and sacrificed everything for me, wouldn't be in vain. But I was falling short on my promise.

This year marks 20 years since the Rwandan genocide -- the world's greatest humanitarian tragedy of the late 20th century. The international community had pledged 'never again' in the aftermath of the genocide in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s. Yet, we are witnessing today a different type of humanitarian disaster unfolding in Syria and Iraq.