Top 1200 Science Fiction Quotes & Sayings - Page 20

Explore popular Science Fiction quotes.

Last updated on December 4, 2024.

Mathematics has two faces: it is the rigorous science of Euclid, but it is also something else. Mathematics presented in the Euclidean way appears as a systematic, deductive science; but mathematics in the making appears as an experimental, inductive science. Both aspects are as old as the science of mathematics itself.

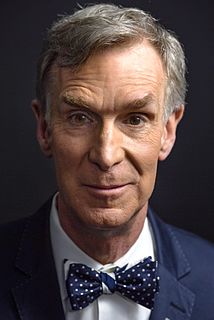

Science is the key to our future, and if you don’t believe in science, then you’re holding everybody back. And it’s fine if you as an adult want to run around pretending or claiming that you don’t believe in evolution, but if we educate a generation of people who don’t believe in science, that’s a recipe for disaster. We talk about the Internet. That comes from science. Weather forecasting. That comes from science. The main idea in all of biology is evolution. To not teach it to our young people is wrong.

It is science alone that can solve the problems of hunger and poverty, of insanitation and illiteracy, of superstition and deadening custom and tradition, of vast resources running to waste, or a rich country inhabited by starving people... Who indeed could afford to ignore science today? At every turn we have to seek its aid... The future belongs to science and those who make friends with science.

The whole point of science is that most of it is uncertain. That's why science is exciting--because we don't know. Science is all about things we don't understand. The public, of course, imagines science is just a set of facts. But it's not. Science is a process of exploring, which is always partial. We explore, and we find out things that we understand. We find out things we thought we understood were wrong. That's how it makes progress.

Now, I'm a failed political consultant. But sometimes fiction has a way of capturing people's imagination in a way that non-fiction doesn't. Conservatives typically haven't written much fiction - specifically political thrillers - over the years to educate, inspire and mobilize people on issues of great import, but we ought to.

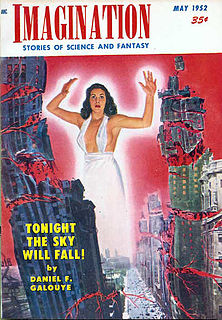

Certainly for me, as an astrobiologist, science fiction has played an important role. One of the quandaries of our field is that we are trying to study and search for something - life - that we can't define in a rigorous way. We only have one example of a biosphere, so we can't really give a good definition.