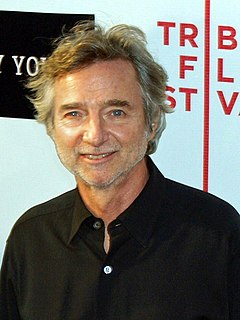

Top 72 Quotes & Sayings by Curtis Hanson

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American director Curtis Hanson.

Last updated on April 18, 2025.

Roger [Corman] didn't actually hire me, though. I was hired by AIP [American International Pictures], the studio that made the picture, which was Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson. It was a great learning experience for me, because not only did I work on the script, but they hired me back to go on location when they were making the movie, to write new scenes and so forth.

On the surface, Wonder Boys seemed like such a departure from L.A. Confidential - it's funny, it's contemporary, and so on - and yet at a certain point, I had a feeling that reminded me how I felt when I was shooting L.A. Confidential. I analyzed it for a while, and thought about how emotionally involved I was with the characters. Then I realized that in both movies, there are three main male characters and one female, and all of them are struggling to figure out what they're doing with their lives, independent of each other.

I was never a critic. I was a journalist and wrote about filmmakers, but I didn't review movies per se. I make that distinction only because I came to it strictly as someone who was just a lover of storytellers and cinematic storytellers. And I still am. I'm still a great movie fan, and I ,that love of movies is very much alive in me. I approach the movies I make as a movie-lover as much as a movie-maker.

It was just a wonderful experience, one for the memory book for sure. The sad thing about it was that the picture came under this absurd cloud of controversy. Here was a movie based on the central theme that racism is something that is taught, and it's illustrated by this story of a dog and the efforts of humans to re-train it after it had been trained to go after black people. And it created this ridiculous controversy and wound up being the last Hollywood movie that Sam [Fuller] made.

Movie stars exaggerate certain things to let the audience know they're just playing a character, as if they're saying, "Look at me, I'm not really an old man, I'm just playing one." Or "I'm not really a homosexual, I'm just playing a gay character. Or an alcoholic. Or somebody who's mentally impaired." They often do it very successfully and win awards for it.

Of course, Sam [Fuller] was like, "No problem," because he treated it like a newspaper deadline. We worked long hours, often very late into the night, in his garage, which had been converted into an office. It was freezing cold outside and there was no heat in the garage, so he had a little space heater over by his side and I had a blanket that he graciously gave me to drape around my shoulders like a Navajo Indian. And he gave me cigars, too, of course.

I never intended to have a career as a journalist, writing about people who make movies. I did it as something that was really rewarding to do, given the opportunity to express myself about something I cared about, and also to learn a lot by watching filmmakers I admired. In a sense, it was my film school. After doing it for a few years, I decided that the time had come to get it together and do some work of my own. Even for a cheap movie, you need film stock and equipment and actors. Whereas to write, all you need is paper and an idea, so I felt that writing might be my stepping stone.

I did it [photojournalism] as something that was really rewarding to do, given the opportunity to express myself about something I cared about, and also to learn a lot by watching filmmakers I admired. In a sense, it was my film school. After doing it for a few years, I decided that the time had come to get it together and do some work of my own. So I stopped doing that and wrote some screenplays on speculation, because even though I wanted to direct, to direct you need a lot of money.

I also got to know Roger Corman a bit while we were on location in Mendocino. And then, subsequently, a woman who also worked on The Dunwich Horror named Tamara Asseyev and I teamed up and co-produced a picture that I wrote and directed, called Sweet Kill, that Roger Corman's then-new company distributed.

Initially, it connected with me when I was a kid, seeing a lot of movies while growing up in Los Angeles. And Sam's [Fuller] pictures are an expression of such a distinct voice that he was one of those filmmakers who made me aware that there was, in fact, a real presence behind the camera that was telling the story, as opposed to actors just presenting it.

There are many people who want to make movies and very few opportunities for them to do it. I had a checkered early career with a lot of very unhappy experiences where pictures got taken away, re-cut, re-titled... all the nightmares one hears about. Consequently, it's so gratifying to then make a picture that's successful and gives you leverage to have better circumstances than you've ever had, before the next time out.

From my point of view, when I was thinking about the prospect of [Michael Douglas] in this part, I wondered if he would go all the way with it. The reason I was concerned is that, oftentimes, actors - especially movie stars - when they're playing a character who might be perceived as unattractive or eccentric, will wink at the audience while they're doing it.