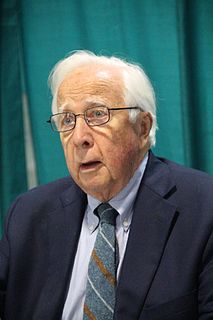

Top 100 Quotes & Sayings by David Olusoga

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a British historian David Olusoga.

Last updated on April 21, 2025.

Public buildings, built from the rates and taxes paid by past generations, are being auctioned off by impoverished councils who need the money to pay the redundancies of workers they can no longer afford to employ. Many of these grand Victorian buildings will be turned into flats that most people will never be able to afford.