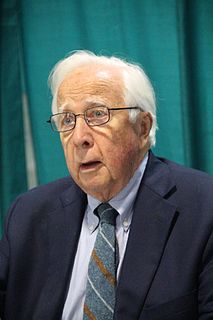

Top 92 Quotes & Sayings by Simon Schama

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a British historian Simon Schama.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

I did an audiobook for 'Rough Crossings,' which I thought was one of the best books I had published. But it was an absolute embarrassment to read it. All these horrible mucked-up bits of syntax, over-the-top adjectives. I found myself editing it while reading. Alert listeners will notice the difference.

Growing up in Britain as a rather loose Jew, the two things that didn't belong together were freedom and religious intensity. In America, they do. The Founding Fathers made a bet that if you didn't force everyone to profess religion in their own particular way, you could protect intellectual freedom, and religion would flourish.

I was conscious of being wordy as a child. I was a terrible talker. I memorised the Latin names of flowers at five; I was shown off as a freak. My father encouraged me to be wordier than I was: he'd been a street orator at the time of Mosley, and his ideal primary concert speech was Henry V's speech before Harfleur.

You are not thinking hard enough if you are sleeping well. And you would have to be unhinged to take on a subject like the French Revolution, or Rembrandt, and not feel some trepidation. There is always the possibility that you will crash and burn, and the whole thing will be a horrible, vulgar, self-indulgent mess.

The history of the Jews has been written overwhelmingly by scholars of texts - understandably given the formative nature of the Bible and the Talmud. Seeing Jewish history through artifacts, architecture and images is still a young but spectacularly flourishing discipline that's changing the whole story.