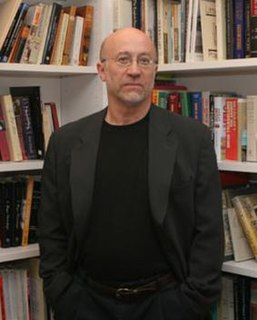

Top 86 Quotes & Sayings by Tony Judt

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a British historian Tony Judt.

Last updated on November 22, 2024.

I just like being on my own on trains, traveling. I spent all my pocket money travelling the London Underground and Southern Railway, what used to be the Western region, and in Europe as much as I could afford it. My parents used to think I was going places, but I wasn't, I was just travelling the trains.

I see myself as, first and above all, a teacher of history; next, a writer of European history; next, a commentator on European affairs; next, a public intellectual voice within the American left; and only then an occasional, opportunistic participant in the pained American discussion of the Jewish matter.

I started work on my first French history book in 1969; on 'Socialism in Provence' in 1974; and on the essays in Marxism and the French Left in 1978. Conversely, my first non-academic publication, a review in the 'TLS', did not come until the late 1980s, and it was not until 1993 that I published my first piece in the 'New York Review.'

Popularizing - much less venturing beyond one's secure turf - was frowned upon for many years. I think I probably internalized the prohibition, even though I was - and knew I was - among the best speakers and writers of my age cohort. I don't mean I was the best historian - a quite different measure.

Undergraduates today can select from a swathe of identity studies.... The shortcoming of all these para-academic programs is not that they concentrate on a given ethnic or geographical minority; it is that they encourage members of that minority to study themselves - thereby simultaneously negating the goals of a liberal education and reinforcing the sectarian and ghetto mentalities they purport to undermine.