A Quote by Barbara Tuchman

What his imagination is to the poet, facts are to the historian. His exercise of judgment comes in their selection, his art in their arrangement.

Related Quotes

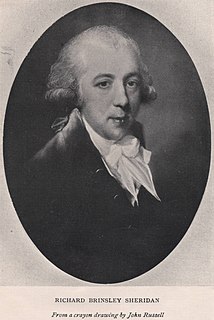

So, then, the best of the historian is subject to the poet; for whatsoever action or faction, whatsoever counsel, policy, or war-stratagem the historian is bound to recite, that may the poet, if he list, with his imitation make his own, beautifying it both for further teaching and more delighting, as it pleaseth him; having all, from Dante’s Heaven to his Hell, under the authority of his pen.

It is unwise to equate scientific activity with what we call reason, poetic activity with what we call imagination. Without the imaginative leap from facts to generalisation, no theoretic discovery in science is made. The poet, on the other hand, must not imagine but reason--that is to say, he must exercise a great deal of consciously directed thought in the selection and rejection of his data: there is a technical logic, a poetic reasoning in his choice of the words, rhythms and images by which a poem's coherence is achieved.

A perfect historian must possess an imagination sufficiently powerful to make his narrative affecting and picturesque; yet he must control it so absolutely as to content himself with the materials which he finds, and to refrain from supplying deficiencies by additions of his own. He must be a profound and ingenious reasoner; yet he must possess sufficient self-command to abstain from casting his facts in the mould of his hypothesis.

The more closely the author thinks of why he wrote, the more he comes to regard his imagination as a kind of self-generating cement which glued his facts together, and his emotions as a kind of dark and obscure designer of those facts. Reluctantly, he comes to the conclusion that to account for his book is to account for his life.

The poet needs a ground in popular tradition on which he may work, and which, again, may restrain his art within the due temperance. It holds him to the people, supplies a foundation for his edifice; and, in furnishing so much work done to his hand, leaves him at leisure, and in full strength for the audacities of his imagination.

Great abilities are not requisite for an Historian; for in historical composition, all the greatest powers of the human mind are quiescent. He has facts ready to his hand; so there is no exercise of invention. Imagination is not required in any degree; only about as much as is used in the lowest kinds of poetry. Some penetration, accuracy, and coloring, will fit a man for the task, if he can give the application which is necessary.