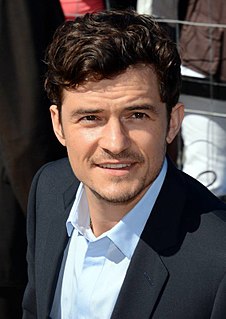

A Quote by Craig Mazin

'Chernobyl' is a human story. It's not a disaster movie. It's not about explosions. It's about people and truths and lies.

Related Quotes

Being aware of truths about what is good or right or about what we ought to do is not the same as deciding what to do. Nor can the former truths be derived from decisions about what to do, or about procedures for making such decisions, unless these procedures themselves rest in some way on the apprehension of truths about what we ought to do.