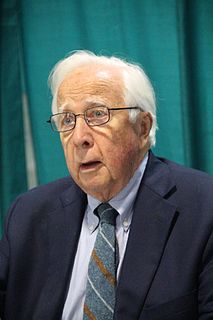

A Quote by Edmund Morgan

The preoccupation of American historical and literary scholars with the New England Puritans must seem to outsiders like an obsession.

Related Quotes

These self-appointed deacons in the Church of Latter-Day American Literature seem to regard generosity (of words) with suspicion, texture with dislike, and any broad literary stroke with outright hate. The result is a strange and arid literary climate where a meaningless little fingernail paring like Nicholson Baker's Vox becomes an object of fascinated debate and dissection, and a truly ambitious American novel like Matthew's Heart of the Country is all but ignored.

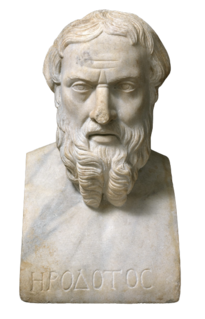

[Sacrifice of Isaac] is a major theme of the so-called Elohist [one authorial strand in the Pentateuch]. It is marked by all of his linguistic characteristics, and so on. We cannot determine what is historical and what isn't. As literary critics, we would understand the importance of this for understanding life, destiny. But the historical question must be left with a question mark.

But if we believe what we profess concerning the worth of the individual, then the idea of individual development within a framework of ethical purpose must become our deepest concern, our national preoccupation, our passion, our obsession. We must think of education as relevant for everyone everywhere - at all ages and in all conditions of life.