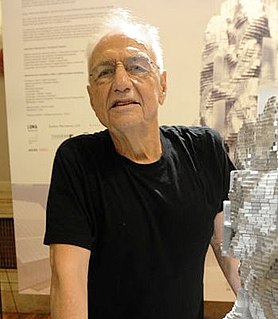

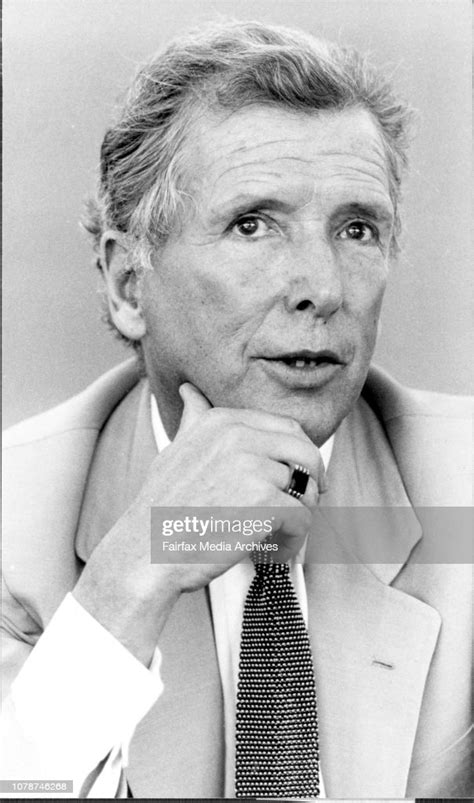

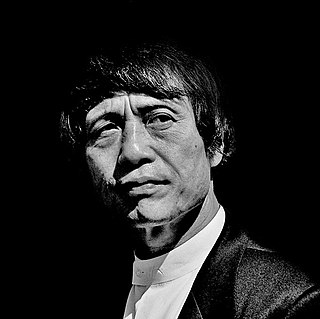

A Quote by Frank Gehry

Most of what's around us is banal. We live with it. We accept it as inevitable.

Related Quotes

Ninety-eight percent are boxes, which tells me that a lot of people are in denial. We live and work in boxes. People don't even notice that. Most of what's around us is banal. We live with it. We accept it as inevitable. People say, "This is the world the way it is, and don't bother me." Then when somebody does something different, real architecture, the push-back is amazing. People resist it. At first it's new and scary.

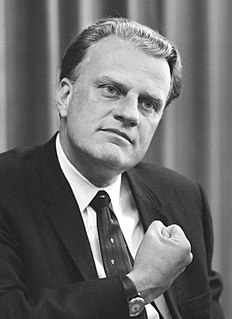

Most of us do not understand nuclear fission, but we accept it. I don't understand television, but I accept it. I don't understand radio, but every week my voice goes out around the world, and I accept it. Why is it so easy to accept all these man-made miracles and so difficult to accept the miracles of the Bible?

If we rail and kick against it and grow bitter, we won't change the inevitable; but we will change ourselves. I know. I have tried it. I once refused to accept an inevitable situation with which I was confronted. I played the fool and railed against it, and rebelled. I turned my nights into hells of insomnia. I brought upon myself everything I didn't want. Finally, after a year of self-torture, I had to accept what I knew from the outset I couldn't possible alter.

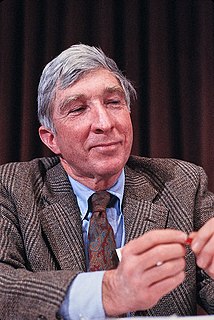

There's a certain kind of conversation you have from time to time at parties in New York about a new book. The word "banal" sometimes rears its by-now banal head; you say "underedited," I say "derivative." The conversation goes around and around various literary criticisms, and by the time it moves on one thing is clear: No one read the book; we just read the reviews.

This is what I thought: for the most banal even to become an adventure, you must (and this is enough) begin to recount it. This is what fools people: a man is always a teller of tales, he sees everything that happens to him through them; and he tries to live his own life as if he were telling a story. But you have to choose: live or tell.