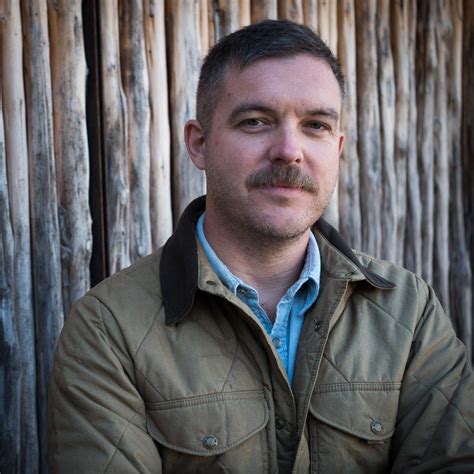

A Quote by Hampton Sides

I find there's a thin, permeable membrane between journalism and history, and though some academic historians take a dim view of it, I gather a lot of strength and professional inspiration from passing back and forth across it.

Related Quotes

Most academic historians accept that historians' own circumstances demand that they tell the story in a particular way, of course. While people wring their hands about 'revisionist' historians; on some level, the correction and amplification of various parts of the past is not 'revisionism' as it is simply the process of any historical writing.

Historians of a generation ago were often shocked by the violence with which scientists rejected the history of their own subject as irrelevant; they could not understand how the members of any academic profession could fail to be intrigued by the study of their own cultural heritage. What these historians did not grasp was that scientists will welcome the history of science only when it has been demonstrated that this discipline can add to our understanding of science itself and thus help to produce, in some sense, better scientists.

I was in the journalism program in college and had some internships in print journalism during the summers. The plan was to go to Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism to learn broadcasting after I graduated. I was enrolled and everything, but ultimately decided that I could never afford to pay back the loan I'd have to take out.

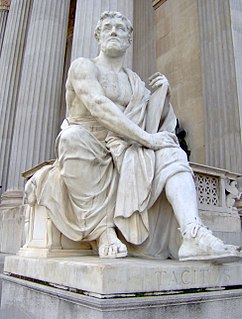

The history of the cosmos

is the history of the struggle of becoming.

When the dim flux of unformed life

struggled, convulsed back and forth upon itself,

and broke at last into light and dark

came into existence as light,

came into existence as cold shadow

then every atom of the cosmos trembled with delight.