A Quote by John Musker

We wanted a musical number that would capture the exhilaration of being out on a boat as they were and sailing with the stars and all that. So that's the origin of We Know the Way. From very early on we said, for an audience that doesn't know this, what we need a song that can really have the kind of sweep and the, you know, pull you in. So that was early on, we conceived of like that should be a musical moment [in Maona].

Related Quotes

I didn't know I wanted to be a hairdresser. I was always interested in fashion and imagery in a very naive way, but it was always an attraction, like glitter balls. This was in the late '70s, early '80s, so it wasn't like today, where you kind of know all about the industry. Fashion was a very insider industry then - it was very closed. So I didn't really know what I wanted to do.

When I was 18 years old, I went on the road with my dad after I graduated from high school. And we were riding on the tour bus one day, kind of rolling through the South, and he mentioned a song. We started talking about songs, and he mentioned one, and I said I don't know that one. And he mentioned another. I said I don't know that one either, Dad, and he became very alarmed that I didn't know what he considered my own musical genealogy.

You know, like, there's songs like "Valerie" and "Bang Bang Bang" that I was so proud of. And, you know, the level of success that they had - if they were little cult hits meant that, you know, I could sellout Webster Hall or Williamsburg Musical Hall or the El Rey theater in LA. Like, that was having made it to me. So the thought of having a number one song in my own career, like, never even registered.

Working with Monk brought me close to a musical architect of the highest order. I felt I learned from him in every way--through the senses, theoretically, technically. I would talk to Monk about musical problems, and he would sit at the piano and show me the answers just by playing them. I could watch him play and find out the things I wanted to know. Also, I could see a lot of things that I didn't know about at all.

I mean, we were hearing music all the way through the islands. You know, we, when we visit the islands, of course since the islands have been churches have come down, there's a church every two blocks. And so there's music in all these different denominations. So we said, music's gotta play a big part of this movie [Maona] to really capture the culture.

Of course, when you see [ musical numbers] in the movie [Out To Sea ], it's cut into a lot with other scenes, but we shot the number straight through, so here I am doing it, and sitting right in front of me in the audience was Donald O'Connor. And I was, like, "Oh, my God, I can't believe I'm performing a musical number in front of Donald O'Connor," who's one of the greats of the silver screen. But it was a thrilling experience, it really was.

As soon as I was born, my mom said I was humming 'When the Saints Go Marching In,' or something like that, you know? It's in the family. And in that neighborhood [Treme, in New Orleans], I think everybody in the neighborhood has some type of musical influence, even if they don't play instruments or anything. It's the way they talk to you, the way they say your name - it's all musical.

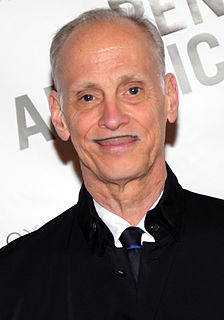

Oddly enough, most of the books written about the subject aren't very good because they just focus on the more hateful movies that they did very early, early on when they were trying to, you know, get Germany into the war, whether it be anti-Semitic movies like "Jud Suss," or "The Eternal Jew," or movies made against the Polish to help, you know, create sympathy for them to invade Poland. You know, there'd be movies where there would be some German girl living in Poland who's raped by the Polish or something.

I'd been taught from an early age that I was in the 'other' category on the standardized tests. You know, I had to go down the checklist - Caucasian, African-American, Latino, Asian-Pacific Islander, and then, you know, at the bottom is other. So, you know, very early on I was taught, in a way, that I was somehow this anomaly.

I'd been taught from an early age that I was in the other category on the standardized tests. You know, I had to go down the checklist - Caucasian, African-American, Latino, Asian-Pacific Islander, and then, you know, at the bottom is other. So, you know, very early on I was taught, in a way, that I was somehow this anomaly.