A Quote by Matthew Heineman

For 'City of Ghosts,' I really didn't speak any Arabic. It obviously made it more difficult, but I also found it to be an advantage while shooting. It allowed me to focus on the emotion of the scene as opposed to just chasing dialogue.

Related Quotes

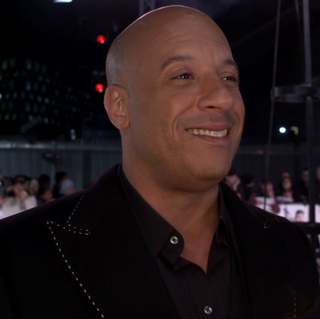

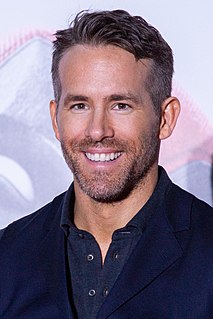

We [ with Russel Crowe] had an Arabic coach there [ in the Body of Lies] that was really helpful, because it was more so than any accent. You have to be so exact, and there's different dialects of Arabic from country to country so it was really, really difficult to tell you the truth. And one of the hardest things I've ever had to do language-wise, because it comes from the throat. It's different. And also learning about the customs and the culture and all that, so we had advisors for that sort of thing.

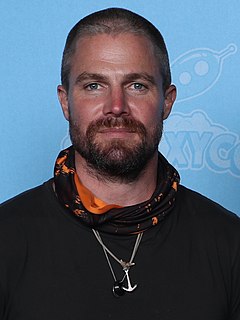

Fight sequence to me isn't just about the athleticism. It so often is about what the emotion that is behind it and how willing you are to really, really challenge that emotion or really take that emotion to that place so you're feeling a certain intensity for the whole time when you're shooting the actual physical scenes.

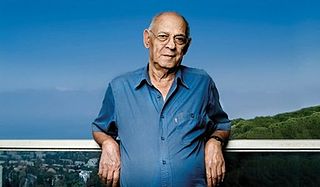

There in front of me was the Senator on the floor being held by the busboy. There was nobody else around, and I made my first frame, and I forgot to focus the camera. The second frame was a little more in focus... then just for a second, while everything was open, the busboy looked up, and he had this look in his eye. I made that picture, and then suddenly the whole situation closed in again. And it became bedlam.(On the 1968 shooting of U.S. presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy.)

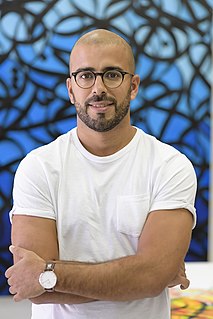

I couldn't know about my culture, my history, without learning the language, so I started learning Arabic - reading, writing. I used to speak Arabic before that, but Tunisian Arabic dialect. Step by step, I discovered calligraphy. I painted before and I just brought the calligraphy into my artwork. That's how everything started. The funny thing is the fact that going back to my roots made me feel French.

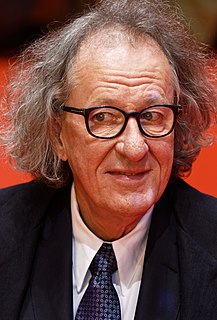

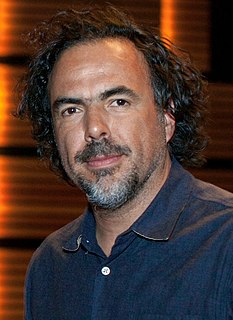

Rewriting isn't just about dialogue, it's the order of the scenes, how you finish a scene, how you get into a scene. All these final decisions are best made when you're there, watching. It's really enjoyable, but you've got to be there at the director's invitation. You can't just barge in and say, "I'm the writer."

Obviously, the US does not want a shooting war with North Korea. But there has to be some path out of this situation that is also presented that is peaceful. We have sanctions, we have deterrence, but the third leg of any resolution to this problem has to be dialogue. It seems prudent for the US to not only threaten North Korea, but to also offer a way forward.

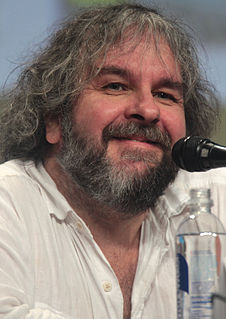

It's often frustrating when you're a war reporter and you're covering these places that far away. You're frustrated by making stories that people can't connect to in any way. It's hard for Americans to connect to Arabic-speaking Iraqis in refugee camps or Pashto-speaking Afghans in the countryside, and having a character who is a vehicle through which you're allowed to make these relationships really allowed us to gain in an emotional weight that was difficult for us to do any other way to make it all human.

On the whole, dialogue is the most difficult thing, without any doubt. It's very difficult, unfortunately. You have to detach yourself from the notion of a lifelike quality. You see, actually lifelike, tape-recorded dialogue like this has very little to do with good novel dialogue. It's a matter of getting that awful tyranny of mimesis out of your mind, which is difficult.