A Quote by Robert Darnton

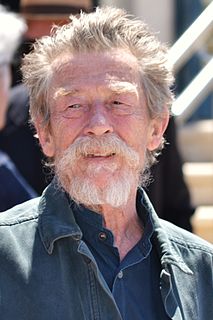

The notion of 'history from below' hit the history profession in England very hard around the time I came to Oxford in the early 1960s.

Related Quotes

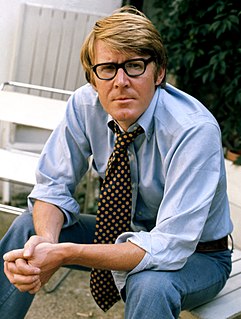

My experience came before most of you were born. My school was a state school in Leeds and the headmaster usually sent students to Leeds University but he didn't normally send them to Oxford or Cambridge. But the headmaster happened to have been to Cambridge and decided to try and push some of us towards Oxford and Cambridge. So, half a dozen of us tried - not all of us in history - and we all eventually got in. So, to that extent, it [The History Boys] comes out of my own experience.

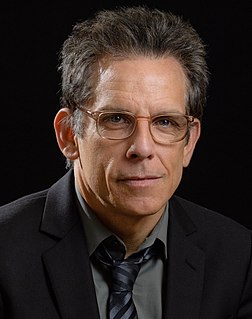

Malibu history is interesting to me. My mom's family was one of the early families in California, so there's history going back to the 1840s or '50s. They came over in the Gold Rush, actually. I have all this guilt about raising my daughter in the East. Coco's very anti-California. It's her way of rebelling.

I was born in England and went to school there. That's when I discovered my undying passion for history - not just for the Middle Ages, but all periods of history. My favorites are medieval, Elizabethan, and Georgian; however, I've written stories set in periods as early as ancient Rome, right up to the Victorian era.

Turned the wrong way around, the relentless unforeseen was what we schoolchildren studied in "History", harmless history, where everything unexpected in its own time is chronicled on the page as inevitable. The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic.

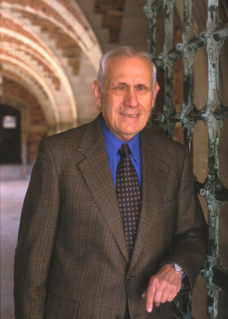

When I came to write my Thomas Cromwell books, I moved onto the center ground of English history, but I was never there before. I didn't feel it was my history particularly, coming from Northern Britain, being of Irish extraction, being a cradle Catholic. The image of England I grew up with felt somewhere else. There was an official England in postcards, but it wasn't one I had visited. But I decided to march onto the center ground and occupy it whether it was mine or not.