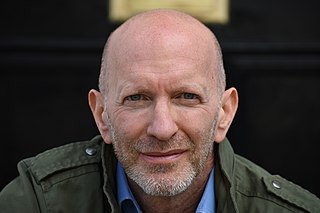

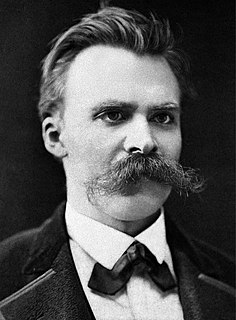

A Quote by Simon Sebag Montefiore

Historical fiction is simply fiction set in the past, and should be judged as such.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

It remains a mystery to me why some of that [pulp] fiction should be judged inferior to the rafts and rafts of bad social [literary] fiction which continues to be treated by literary editors as if it were somehow superior, or at least worthier of our attention. The careerist literary imperialism of the Bloomsbury years did a lot to produce fiction's present unseemly polarities.

"Hard" science fiction probes alternative possible futures by means of reasoned extrapolations in much the same way that good historical fiction reconstructs the probable past. Even far-out fantasy can present a significant test of human values exposed to a new environment. Deriving its most cogent ideas from the tension between permanence and change, science fiction combines the diversions of novelty with its pertinent kind of realism.

As you see, I bear some resentment and some scars from the years of anti-genre bigotry. My own fiction, which moves freely around among realism, magical realism, science fiction, fantasy of various kinds, historical fiction, young adult fiction, parable, and other subgenres, to the point where much of it is ungenrifiable, all got shoved into the Sci Fi wastebasket or labeled as kiddilit - subliterature.

Writers of historical fiction are often faced with a problem: if they include real-life people, how do they ensure that their make-believe world isn't dwarfed by truth? The question loomed large as I began reading 'The Black Tower', Louis Bayard's third foray into historical fiction and fifth novel overall.