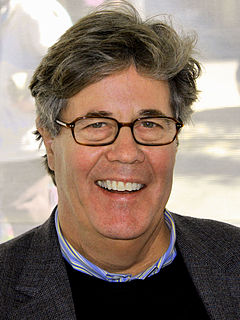

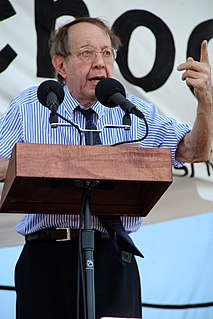

A Quote by Tony Evans

When I heard Martin Luther King's speech, 'I Have a Dream,' I reflected on the fact that much of the success of that movement was driven by the unity of the church.

Related Quotes

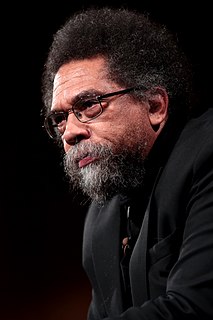

What is accurately portrayed is the rich humanity not just of Martin Luther King but of the movement, which was a multiracial movement. You had blacks and whites coming together and sacrificing, organizing and mobilizing the world. That's the first time we've had collective action put at the center of any kind of portrayal of Martin King on the screen.

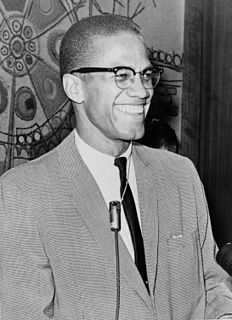

The white man supports Reverend Martin Luther King, subsidizes Reverend Martin Luther King, so that Reverend Martin Luther King can continue to teach the Negroes to be defenseless - that's what you mean by nonviolent - be defenseless in the face of one of the most cruel beasts that has ever taken people into captivity - that's this American white man, and they have proved it throughout the country by the police dogs and the police clubs.

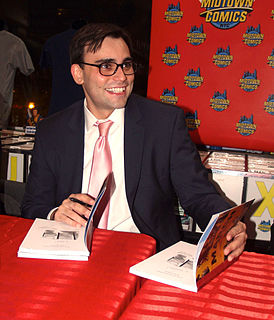

Martin Luther King's 1963 'I have a dream' speech was a thrilling milestone in the civil rights movement, so enduring that we tend to attribute its searing power to a kind of magic. But Gary Younge's meditative retrospection on its significance reminds us of all the micro-moments of transformation behind the scenes--the thought and preparation, vision and revision--whose currency fed that magnificent lightning bolt in history.

Martin Luther King really was a safety valve for white people. Any time it appeared that the black community was on the verge of really doing what we ought to do based on having been attacked, they put Martin Luther King on television. He was always saying, "We must use nonviolence. We must overcome hate with love." White people loved that. That's why they gave him a Nobel Prize. But when Martin Luther King started condemning the Vietnam War, that's when white people turned against him.