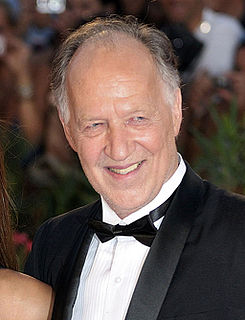

A Quote by Werner Herzog

That shot in "Into the Inferno" somehow popped up while my editor and I were viewing the footage. I immediately said, "That looks like the opening shot because the camera approaches the action very slowly and we have enough time to insert some of the main credits into it." So it was a practical choice. At the same time, you see these tiny figures standing at the rim of something, and all of a sudden, the camera rises further and you find yourself looking straight down into an inferno.

Quote Topics

Action

Approaches

Because

Camera

Choice

Credits

Down

Editor

Enough

Enough Time

Figures

Find

Footage

Further

Immediately

Inferno

Insert

Like

Looking

Looks

Main

Opening

Practical

Rim

Rises

Said

Same

Same Time

See

Shot

Slowly

Some

Somehow

Something

Standing

Straight

Sudden

Time

Tiny

Up

Very

Viewing

Were

While

Yourself

Related Quotes

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.

I had a rope around my waist, and the rope was attached into the helicopter in case I fell off. And the shot was a shot that began with Kim Novak going out of a house and getting into a bus. Then it was supposed to go over the countryside and find a freight train on which Bill Holden was standing. And then after seeing a good look at the freight train, the camera was supposed to move up into the sky for the end credits.

Jack [Nicholson] really knows about the camera. He's one of the directors who likes to play with the camera. He'll change things around, play with lighting, things like that. He'll even spend hours on the set-up for an insert shot. He's an interested person who gets involved in all the aspects of the films he is making.

Onstage, I enjoy the thrill of live performance - there is no substitute for that rush. On camera I enjoy the crafting of a scene, the widespread creative marksmanship happening all around you for every second of footage. Onstage you can suddenly feel solitary, like it's all on your shoulders, while on camera you feel like there are so many people working with you on every shot. Those are each unique and gratifying challenges.

When you're in a two-shot together, you can't be the same as when you're both in singles. Try as you will, it cannot be the same as when you're in the shot together. It simply cannot be. It's physically impossible. You're behind the camera desperately wanting to help your colleague. When it's just you, on your own, it can be self-conscious in a way that you're not when we're just talking, you and I, and then all of a sudden it's me and then it's you. The two-shots were probably more natural.

Because of the way that I work with the actors and because a scene is not in this rigid and literal interpretation of something written, I can constantly change stuff, which means I can get a scene absolutely perfect, and then when we go to shoot it, the requirements of the shot mean it would be useful to extend the dialogue or take a line out or swap things around. So the camera doesn't serve the action. The action serves the camera. That's important. So it becomes more and more organic and integrated.