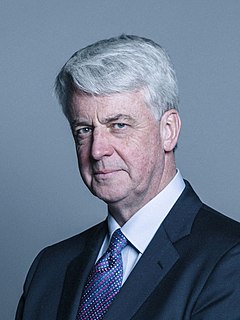

A Quote by David Olusoga

It was through watching documentaries on the BBC in the late 1980s that I first became interested in art and history.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

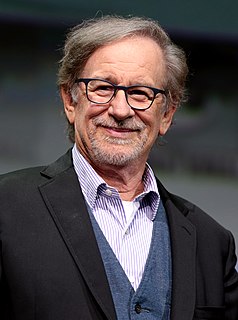

There's no other way to learn about it, except through documentaries. I encourage documentarians to continue telling stories about World War II. I think documentaries are the greatest way to educate an entire generation that doesn't often look back to learn anything about the history that provided a safe haven for so many of us today. Documentaries are the first line of education, and the second line of education is dramatization, such as The Pacific.

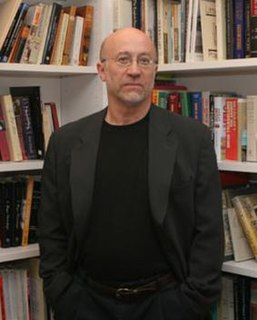

I started work on my first French history book in 1969; on 'Socialism in Provence' in 1974; and on the essays in Marxism and the French Left in 1978. Conversely, my first non-academic publication, a review in the 'TLS', did not come until the late 1980s, and it was not until 1993 that I published my first piece in the 'New York Review.'

Jonathan Meese is not interested in the history of reality. Everything radical and precisely graphic is sustainable. Human ideologies like religions and politics are based on the past and therefore irrelevant to art. Art always transforms radicalism of the past into the future. Art is always the total time machine. Jonathan Meese is interested in the history of the future. Art is never nostalgic.

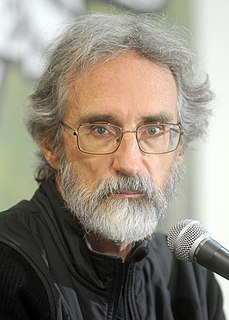

A publisher friend of mine suggested that I write a book about my grandfather, who had just died. I had nothing else to fill my empty days with, so I started work on this book. While researching it - watching lots of movies, talking to moviemakers - I became interested in movies and started making documentaries.

What I found interesting about Slava Fetisov was that he went through three different generations of Soviet hockey. In the late 70's, he experienced the Miracle on Ice, and then in the 80's became with his teammates the Russian Five, the most dominant team in the history of hockey, and then helped bring down the hockey system when the Soviet Union collapsed and became one of the first players to play in the NHL, and then ultimately came back to Russia.

Growing up in the '70s and '80s when my dad had an art gallery, one of the things that frustrated me was the world seemed so tiny, and to appreciate contemporary art, you needed a history of art, a formal education. I was more interested in the people, and that's why I went into the movie business in the first place.